A Christmas Eve Roundup

Two big legal/political stories need some fleshing out

Hello from charming Kingston, NY! I’m up here with family for the week, and we’re all enjoying the sound of babies, the sight of dogs romping in the snow, and the sharing of generational stories among cousins, uncles and aunties.

Several big stories broke this week, including a long-awaited SCOTUS ruling on the legality of Trump’s troop deployments. As I’ll discuss below, this caught many by surprise (in a good way), given the Court’s recent pattern of finding any reason at all to back the regime and its unconstitutional and illegal actions.

I’ll also cover some of what the Epstein files have revealed in the DOJ’s second big release. The release included documents indicating the FBI had identified 10 Epstein co-conspirators, directly undermining Kash Patel’s sworn testimony before Congress. Several other documents allege Trump committed very serious crimes.

As to the latter, I want to proceed cautiously given that the FBI receives many allegations, and allegations alone are not actionable without proof. That doesn’t mean, however, that the public perception of Trump won’t be further damaged.

SCOTUS rules against Trump on federal troops

In a 6-3 ruling, with the usual radicals dissenting (Justices Alito, Thomas and Gorsuch), the Supreme Court found that President Trump’s deployment of federal troops to Illinois was illegal under Title 10. This is a huge blow to Trump’s plans to co-opt state national guards in service of his fascist project.

The way the Court got there wasn’t by reviewing whether Trump’s declaration of a “rebellion” that had to be put down was legit. Rather, it followed the reasoning of an amicus brief by Prof. Marty Lederman of Georgetown University, who argued that the language of Title 10 foreclosed use of the National Guard if Trump had not determined that the U.S. military was unable on its own to put down the “rebellion.”

When I’d read that amicus brief at the time, I was quite persuaded by it. This is what I wrote in a social media post about Prof. Lederman’s argument at the time:

For you law geeks out there, as Prof. Steve Vladeck wrote today in his column, there’s a possible wild twist on the national guard cases.

Per Vladeck, Professor Marty Lederman of Georgetown University “argued quite persuasively in an amicus brief filed in the Supreme Court in the Illinois case that there’s a pretty good argument that the lower courts have largely sidestepped that would make all of these cases much easier.”

He explained the argument as follows:

To federalize National Guard troops under 10 U.S.C. § 12406(3), the President must determine that he “is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.” The lower courts have assumed, to date, that “regular forces” includes civilian law enforcement personnel. As Professor Lederman powerfully explains, that can’t possibly be correct; there is significant textual and contextual support for the proposition that “the regular forces” is a reference to the active service federal military. And because there has been no effort “to execute the laws of the United States” with those forces (and no finding that the President is unable to do so), the invocations of § 12406(3) could be struck down on far simpler (and less fraught) grounds than what it really means for the President to be “unable” to enforce federal law, and who decides that question.

I dove into the amicus brief because I am in fact a law nerd. Lederman notes something interesting (and try not to laugh at the “Dick Act” like we’re 12):

Congress enacted the original version of § 12406(3) as part of the Militia Act of 1903, commonly known as the Dick Act (so-named after Representative Charles Dick, Chair of the House Committee on Militia). See Act of Jan. 21, 1903, ch. 196, § 4, 32 Stat. 775, 776. The principal purpose of that legislation was to establish, organize and subsidize a well-trained, well-equipped and efficient militia that could be called into federal service to effectively supplement the efforts of the standing military, whose forces were commonly referred to as “Regulars.” This initiative was important because the nascent organized militia that Congress had provided for calling forth back in 1792 had “proved to be a decidedly unreliable fighting force.”

In his first annual message to Congress, on December 3, 1901, President Roosevelt described the nation’s militia law as “obsolete and worthless.” … In the absence of an effective federal militia, Congress and the President had to resort to using units of temporary volunteers to supplement the regular armed forces, including in wars overseas. See, e.g., Act of Apr. 22, 1898, ch. 187, §§ 2-5, 30 Stat. 361, 361 (declaring that “in time of war the Army shall consist of two branches which shall be designated, respectively, as the Regular Army and the Volunteer Army of the United States”; defining the “Regular Army” as the permanent military establishment”; and establishing a process by which the President could ask Congress to raise a Volunteer “force”). Many of those volunteer units lacked proper or sufficient training, organization and readiness. President Roosevelt therefore implored Congress to remedy the situation by establishing a means by which the states’ militia could be enhanced and effectively called into federal service. Of particular significance for purposes of this case, Roosevelt urged Congress to ensure that the organization and armament of the new federalized national militia “be made identical with those provided for the regular forces.”

See that last term? That refers to the permanent federal army.

He later writes,

There can hardly be any question that the term “the regular forces” in the 1908 Act— which has remained in the statute ever since, appearing today in 10 U.S.C. § 12406(3)—referred to the standing, professional military forces, who were commonly known as “Regulars.” The effect of the law was to prescribe the National Guard as the “second line of defense,” S. Rep. 61-216, at 1, i.e., as a supplement to the regular army. Requiring the President first to make use of “the regular” military forces, and to mobilize the National Guard only if and when those regular forces were inadequate to the task, helped to ensure that the militia remained subject to state control except where necessary.

Because Trump never called upon the regular forces to do anything in Chicago, nor even considered whether they would be insufficient to quell the “rebellion” there, he can’t federalize the National Guard to try to take care of things. Statute says so!

Of course, this opens a different can of worms. Under what circumstances would the president be permitted to send in the “regular forces”?

Professor Lederman has a good answer to this, too:

Moreover, on any plausible understanding of what it means to be “unable” to execute federal laws, it is difficult to imagine that the President would be “unable” to ensure faithful execution of those laws if he were to first deploy regular military forces to assist ICE, assuming a sufficient number of such forces were available to perform that function.

In other words, Trump would have to conclude that the regular army could not have handled the “rebellion” and therefore state national guard was needed. That is patently absurd, given the size and scale of the protests in Chicago.

An interesting take, and an off-ramp for the Supreme Court to toss this case back to the trial court for a determination, if it doesn’t want to deal with the big question!

Wouldn’t you know it, this is precisely the argument the Court majority latched onto in concluding that Trump’s troop deployments were illegal under Title 10. In its unsigned, three-page decision, the Court’s majority wrote,

We conclude that the term “regular forces” in § 12406(3) likely refers to the regular forces of the United States military. This interpretation means that to call the Guard into active federal service under § 12406(3), the President must be “unable” with the regular military “to execute the laws of the United States.” Because the statute requires an assessment of the military’s ability to execute the laws, it likely applies only where the military could legally execute the laws. Such circumstances are exceptional: Under the Posse Comitatus Act, the military is prohibited from “execut[ing] the laws” “except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress.” 18 U. S. C. § 1385. So before the President can federalize the Guard under § 12406(3), he likely must have statutory or constitutional authority to execute the laws with the regular military and must be “unable” with those forces to perform that function.

This of course directly raises the question over whether Trump could invoke an exception to the Posse Comitatus Act, namely the Insurrection Act. This is something I’ve written about rather extensively, and I won’t review the legal issues here.

But I do think we should view the question of the Insurrection Act from a practical standpoint. The big fear out there is that Trump will claim there’s an insurrection and order the federal military into our streets around the midterm elections next year.

While I understand the anxiety around that, it’s worth playing out what that would actually look like. Three considerations weigh strongly against that option in my view:

There is little chance the federal courts will uphold the use of the Insurrection Act to allow Trump to deploy troops everywhere. At best, he could argue that in certain urban areas, there is unrest rising to the level of a “rebellion.” That’s not going to make a big enough difference to a national election.

The federal courts already shot down a claim of “rebellion” where only peaceful street protest exists. District courts could quickly enjoin Trump troop deployments to urban areas under these precedents and order the troops out, and there may not even be time for SCOTUS to weigh in before the elections are held without their presence.

Next year’s election is a midterm election where GOP control of the House is what Trump most fears losing. He dreads Democratic-led congressional investigations, hearings and possible impeachment. Notably, the House races that will determine the majority are not typically in the same urban strongholds where Democrats already hold the seats. Rather, they are usually in suburban districts where there are usually no protests at all. Trump can’t possibly deploy the U.S. military everywhere in these suburban areas sufficiently to impact House elections. Indeed, any attempt to do so would probably drive turnout even higher among Dems and anti-Trump independents.

Trump is far more likely to turn our collective attention to the U.S. military’s actions in Venezuela, where he is still operating without any restraints from the GOP-Congress. The days of him threatening to call in the federalized National Guard to assist ICE and CBP, by contrast, now appear to be drawing to a close.

Epstein files reveals

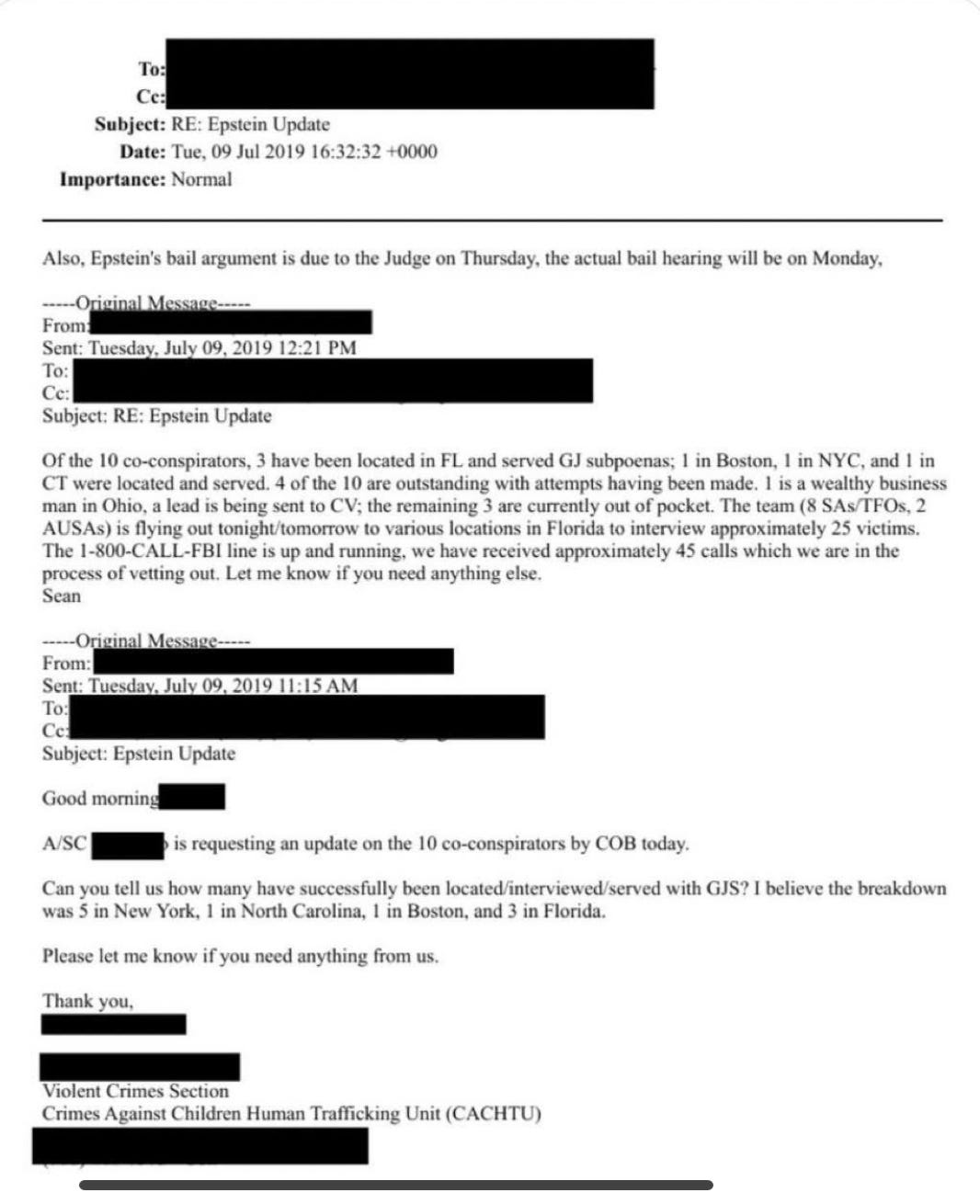

One of the most interesting documents reported on yesterday concerns an internal Justice Department communication from 2019 about Epstein co-conspirators. There are apparently 10 individuals that the FBI had identified, with four of them actually served with papers.

This appears to have been a big team effort. As the author notes, it involved “8 SA/TFOs, 2 AUSAs”—meaning presumably eight special agents/task force officers and two assistant U.S. attorneys reviewing 25 victims. So what became of these co-conspirators? By the sound of this, they were individuals to whom victims were trafficked by Epstein and Maxwell.

Yet Kash Patel had assured Congress, under oath back in September, that no victims had been trafficked to anyone.

Did Patel lie to or mislead Congress? How could he not have been aware of these co-conspirators? Indeed, the DOJ shut down the entire investigation in July, declaring that there would be nothing further done.

There is no basis for redacting the names of the senders and recipients of these emails. Those with knowledge of the investigations need to testify, and the names of the co-conspirators need to be made public. The Epstein Files Transparency Act (EFTA) requires it. Expect a fight ahead.

Finally, I want to remark on some of the more shocking documents produced recently. One of them accuses Trump of rape and involves the alleged murder of a victim. Another, which I discussed briefly yesterday, purports to be a letter sent by Epstein to Larry Nassar, another convicted sexual predator.

The Department of Justice takes the position that the former is merely an allegation, and the latter is a fake. Fair enough; the FBI has in its possession all manner of documents that contain mere allegations or are forgeries, and their production under the EFTA does not mean that they are true. (Notably, the DOJ has no problem making insinuations about other politicians and celebrities without any actual evidence behind them.)

The Epstein files contain many statements and retractions by victims. There are well known reasons why victims retract their accusations, especially when threatened by powerful people. There are also reasons why Trump’s enemies might make unfounded allegations against him, and we need to acknowledge that the files likely contain some of those. Indeed, some of these might be deliberately made to muddy the waters and make actual allegations appear fabricated as well.

Take the Epstein letter to Nassar. There are many questions around its legitimacy, including the fact that this does not match Epstein’s handwriting and was postmarked a few days after his death. CNN reported,

The envelope says it was sent from the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York City to Nassar, who was listed as an inmate at a federal prison in Arizona.

But the DOJ, insisting it is a forgery, notes the postcard was postmarked in Virginia, which leads to some obvious questions. If it is a fake, as the DOJ insists, then who sent it? And why would someone want to imply that Epstein was planning to kill himself in it? Who would benefit from such an implication?

Theories abound, which is why we should proceed cautiously. Did the government investigate whether the handwriting matches that of any of the people around or involved with Epstein? Did Epstein ever speak about or mention Nassar before?

If the government was involved in any way in forging that letter, the public needs to know everything about it.

I misread your reference to Justices Alito, Thomas and Gorsuch to refer, instead, to Alita, Thomas and Grouch. Not sure why I feel a need to share this, but there it is. Ba humbug.

I hope Riley is feeling much better and you are all enjoying your holidays with family and friends.