A Glimmer of Hope

Two developments offer some signs that the judicial system is starting to push back.

You may have noticed that I haven’t written much about legal cases lately. In part that’s because everything in Trump’s criminal matters pretty much froze after the Supreme Court awarded Trump an immunity idol. Then when he won the election and our new national nightmare began, there was the inevitable winding down of the federal cases against him.

Honestly, it was all too depressing and predictable to write about.

With wrecking balls from both SCOTUS and Team Trump destroying legal norms, for us weary defenders of the guardrails and the institutions, hope within the judicial realm has been in short supply.

Until this week.

There are two developments that have legal experts lifting their heads up out of their hands to pay attention. My own eyes lit up when I scoured the legal badlands for any sign of life and spotted two little sprouts poking through the cold ground.

These tiny buds may not represent much just yet, but there they are in writing, and they could begin to represent some actual judicial limits on Trump’s power. It is honestly a bit shocking to see in light of everything we have recently experienced.

So walk out with me into this bitter legal winter air, and let’s inspect these delicate jurisprudential sprouts. As I’ll explain, they grow in two distinct spots, but they share the same rich legal soil.

SCOTUS denies review of the gag order

It was a terse, one sentence order: “The application for stay addressed to Justice Alito and referenced to the Court is denied.”

With that one line, the U.S. Supreme Court, acting through Justice Alito (!!), denied review of a New York ruling that had affirmed the gag order in Trump’s Manhattan criminal case.

Why is this important?

Imagine the opposite for a moment. The Court could have said it wants to issue a stay and to review the gag order imposed by Judge Juan Merchan. And that would have peeled away some of the last vestiges of judicial independence.

If you recall, after the guilty verdict in Trump’s Manhattan criminal case came from the jury, Judge Merchan left in place portions of his gag order limiting what Trump could say about court staff, jurors, prosecutors, or members of their families.

This was the right call by Judge Merchan. After all, Trump is still appealing that case and even asking for the verdict to be thrown out in light of the Supreme Court’s immunity grant, claiming that at least some of the evidence considered by the jury should never have seen the light of day. If Trump were to win that appeal, there might have to be a whole new trial before a whole new jury. Because of that possibility, Trump shouldn’t be permitted to taint the jury pool.

That didn’t stop Trump and his allies from trying to lift the gag order. As Newsweek reported,

Several efforts have been made to have the gag order tossed. An appeals court rejected Trump’s own effort to have it lifted in August. That same month, a long-shot bid from Missouri’s attorney general to have the order removed was also turned down by the Supreme Court.

The denial by the Supreme Court ends this effort. It means the High Court wasn’t sufficiently interested in the First Amendment arguments advanced by Trump’s lawyers in their special petition, nor in the idea that as the president-elect he is entitled to some kind of broader rights.

Seen within an even larger context, as legal analyst Harry Litman observed on his Talking Feds channel, the Supreme Court wasn’t prepared to act proactively to protect Trump from the orders and the power of a New York Superior Court judge, at least when it came to what he could and could not say.

That implicitly means that the judiciary—even a sole judge like Merchan inside a county courtroom—can continue to hold the most powerful man in the country under his sway and answerable to his rulings. Trump remains subject to Judge Merchan’s jurisdiction, and the Supreme Court has effectively signaled it isn’t interested in making an exception to the way things are done when it comes to gag orders, notwithstanding who the defendant is.

Other judges with Trump-related cases are likely taking note. Here was an opportunity for a Trump-friendly SCOTUS to wrest control of the case from a judge, and it passed on that chance without comment. Read broadly, there really is a limit on what the six conservative justices will actively do for Trump, despite the shocking immunity ruling. Allowing the state-level judicial process to work things out, even when the defendant is the president elect, is a major step toward keeping accountability and the rule of law alive.

Bragging rights

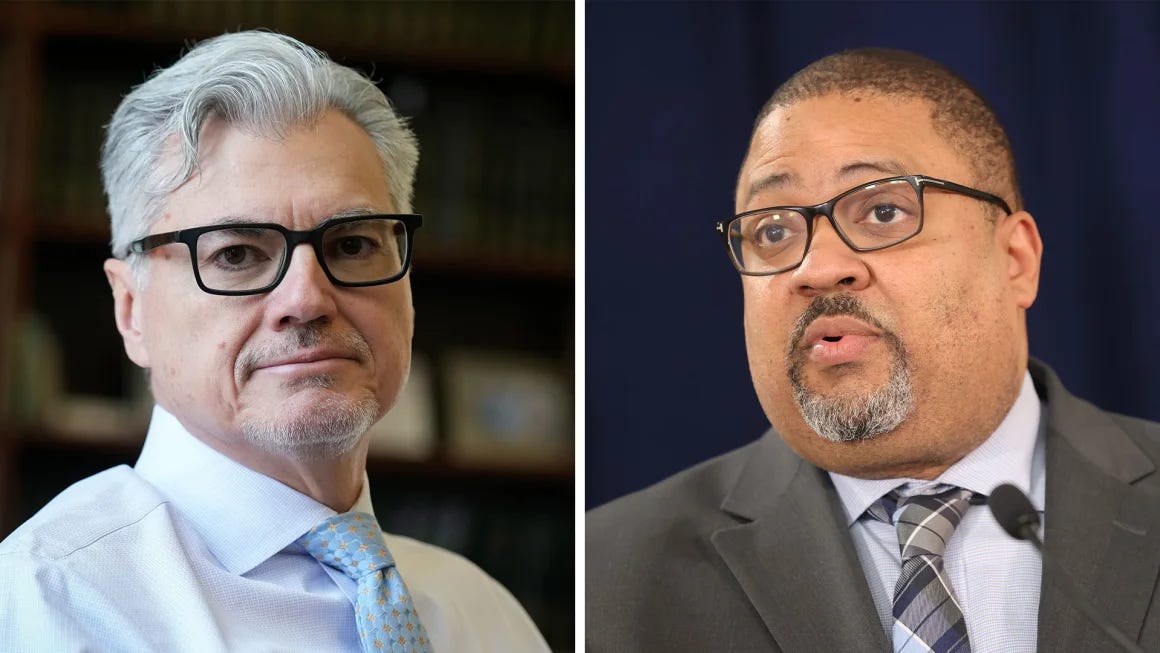

When District Attorney Alvin Bragg filed his case for falsifying business records against Donald Trump, many scoffed and dismissed his actions as inconsequential. Going after the former president for making hush money payments to a porn star, then covering up the trail, seemed like small potatoes, especially stacked next to trying to overturn the election or stealing top government secrets.

And yet perhaps because of the simplicity of his case, Bragg is the only prosecutor to obtain a guilty verdict against Trump before the election. And because Bragg carefully decided to focus on the period before Trump took office, there is not much that SCOTUS’s immunity ruling can do to save Trump or force a do-over.

In retrospect, Bragg’s case now looks clean and straightforward. He brought the charges, presented his evidence, and obtained a guilty verdict from a jury of Trump’s peers.

Trump understandably is now trying hard to get that verdict thrown out. After all, he still faces a sentencing that could hang over his presidency. But he faces some tough hurdles in that quest.

Trump argues that the verdict was tainted by some improper evidence that should have been kept out on immunity grounds, such as when he took meetings while in the Oval Office. But even if that evidence were ignored, there’s still enough from the period before Trump took office to nail him for the same crime. That makes it unlikely the case will get thrown out on immunity grounds. But Trump will manage to buy himself more time while the matter is appealed.

His lawyers are also making the more dangerous argument that the case should be dismissed now that Trump is the president-elect. With Trump winning the election, his lawyers argued that the entire case needs to go, citing Justice Department policies that a president cannot be prosecuted for crimes. After all, Trump will take office on January 20, which is just around the corner. A criminal proceeding is inconsistent with the requirement to allow the chief executive to do his job.

But to make this argument, as legal analyst Norm Eisen notes, Trump’s team “invents a new constitutional category of pre-presidential privileges, arguing that the case must be dismissed” because it “disrupts his transition efforts and his preparations.”

The thing is, there is no such legal rule regarding a president elect. All of the case law and legal reasoning in DoJ opinions center around the president while in office. Indeed, as Eisen points out, until Trump is actually president, there is no reason for the proceedings or the sentencing to be halted.

Bragg agrees. Yesterday, he showed he is made of fairly stern stuff and is willing to go toe-to-toe with the president-elect. Bragg filed a massive, 82-page opposition brief arguing the case should proceed and Trump should be sentenced anyway.

Among his arguments, as Eisen notes in my discussion above, was that immunity should not apply to a president elect. But even after Trump becomes president, Bragg argues, this case is different. Here, the jury has already rendered its verdict. Trump doesn’t have to attend any post-trial proceedings, and he wouldn’t have to serve his sentence, if one is handed down, until after his term is over. It’s hard to see how the post-verdict proceedings would impact his ability to be president in any major way.

Bragg also argues that rather than dismiss the case, Judge Merchan could put the proceedings on ice until after Trump’s term. Or he could permit the proceedings to continue, with the caveat that no evidence from his time in office could be used in the proceedings.

That decision will impact when sentencing takes place. As Joyce Vance noted in her Civil Discourse newsletter, Bragg

flatly rejected Trump’s argument that the Supreme Court’s immunity ruling impacts their case and asked Judge Juan Merchan to proceed to sentencing. Nothing, the DA writes, prevents Trump from being sentenced before the inauguration.

It would admittedly be a baller move to actually hand down a sentence just before the inauguration, even if it’s just probation, especially if Trump is likely to violate its terms.

From a broader sense, it also matters that Bragg is not easing up on Trump at all. On the contrary, he’s saying to Judge Merchan, “Let’s keep going. Let’s get to sentencing and the inevitable appeals.”

Whether Judge Merchan agrees won’t be known until he rules on the motion to dismiss. But Bragg’s brief is a big middle finger to the incoming administration. It’s as if he is saying, “So what if you’re the president elect, I don’t care.” This stand is exactly the kind of steely resolve we need to see from prosecutors.

Assuming the criminal proceedings do not pause until at least Trump’s inauguration, Judge Merchan does have some interesting choices. He can still sentence Trump, perhaps to probation or even to prison, but suspend that sentence until after Trump is out of office. If it’s a prison sentence, this somewhat perversely may encourage Trump to do everything he can to remain in office beyond his constitutionally permitted second term.

Or, Judge Merchan could put off sentencing until after Trump is out of office, creating a kind of sword hanging over Trump even while he appeals the denials of the motions to dismiss. Realistically speaking, Merchan may be far more willing to impose a prison sentence after Trump is out of power because it would be less disruptive to everyone involved.

These two developments—a shrug by SCOTUS on the gag order and some real backbone from a state prosecutor—are not much to hang our hats on yet. They are but the beginnings of what could become the judicial system really pushing back. That they happened at all suggests the judicial system may now be recovering from the shock of the immunity ruling and the election and is willing to begin to assert itself against Trump.

And that would be a welcome development indeed.

The OLC opinion that protects presidential crime is deeply flawed. So is the SCOTUS immunity decision. It assumes presidents will be benevolent and ethical. trump is living proof that a criminal president should not be above the law.

Alvin Bragg is a true American hero. And as I understand it, there’s a difference between federal cases and the state one brought by Bragg. I love that he is standing up to the bully.