A Modest Proposal on Limiting the Filibuster

We should look to history as our guide to when the filibuster should not apply.

The filibuster is on the minds of nearly everyone following politics in America, so I want to offer a possible way forward, one which takes into account the concerns and promises made by the filibuster’s supporters while permitting certain, specific legislative priorities to not wither and die in the Senate because of it.

Three landmark bills aimed at strengthening the civil rights of minority groups in the United States have now passed the House: The Equality Act (extending protections of the Civil Rights Act to LGBTQ Americans), the For the People Act (expanding and protecting the fairness of elections), and the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act (holding authorities more accountable in law enforcement). The latter two were just voted on last night.

All three measures passed along largely party lines, and all three face an uncertain future in the Senate, where they currently will require at least 10 GOP senators to vote for passage under the 60-vote filibuster rule in that chamber.

The Senate Democrats could end the filibuster through a process known informally as “the nuclear option,” which is essentially a change in the way the Senate rules are interpreted. This would require just 50 votes plus a tie-breaker from Vice President Kamala Harris. The nuclear option was used by Democrats to end the filibuster with respect to federal judicial and cabinet-level appointments in 2013, and by the GOP with respect to Supreme Court justice nominees in 2017.

But at least two Democratic Senators—Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Krysten Sinema of Arizona—are on record opposing the elimination of the filibuster for legislative matters, arguing that the provision encourages bipartisan cooperation. As part of his agreement not to hold the Senate business hostage any longer at the start of the Session, minority leader Mitch McConnell exacted assurances from these senators that they would not vote to end the legislative filibuster.

Progressives hope to use the building pressure from these bills, which were long championed by and are very popular with the Democrat base, to pressure Manchin and Sinema to change their minds. If they do not, critics argue, the civil rights agenda will stall, the base will be furious that progress seems impossible even when the Dems control both Congress and the White House for the first time in over a decade, and the party will lose badly in 2022, particularly as the GOP stacks Congress through the very gerrymandering that bills like the For the People Act were drafted to address and prevent.

How do we unstick ourselves from this situation? First, we can take some guidance from the way in which the filibuster rules have been modified by consensus and by both parties when they were in power before. One modification occurred in 1974 with the passage of the Congressional Budgetary Act, which created a process called “budget reconciliation” in which the Senate agreed to fast track legislation related to revenues and expenditures without the ability of either side to filibuster it. And as discussed above, carve-outs for executive-level appointments and Supreme Court justices came in 2013 and 2017. These exceptions demonstrate that it is possible to whittle down the filibuster without voting to end it altogether.

A similar carve-out for specific types of bills—specifically those aimed at strengthening the civil rights and civic participation of traditionally underrepresented and oppressed minorities—is likewise possible without a wholesale discarding of the filibuster mechanism. Such an exception would recognize that these minority groups traditionally have been shut out of the political process and have been effectively marginalized by a small but determined cabal of opposition in government.

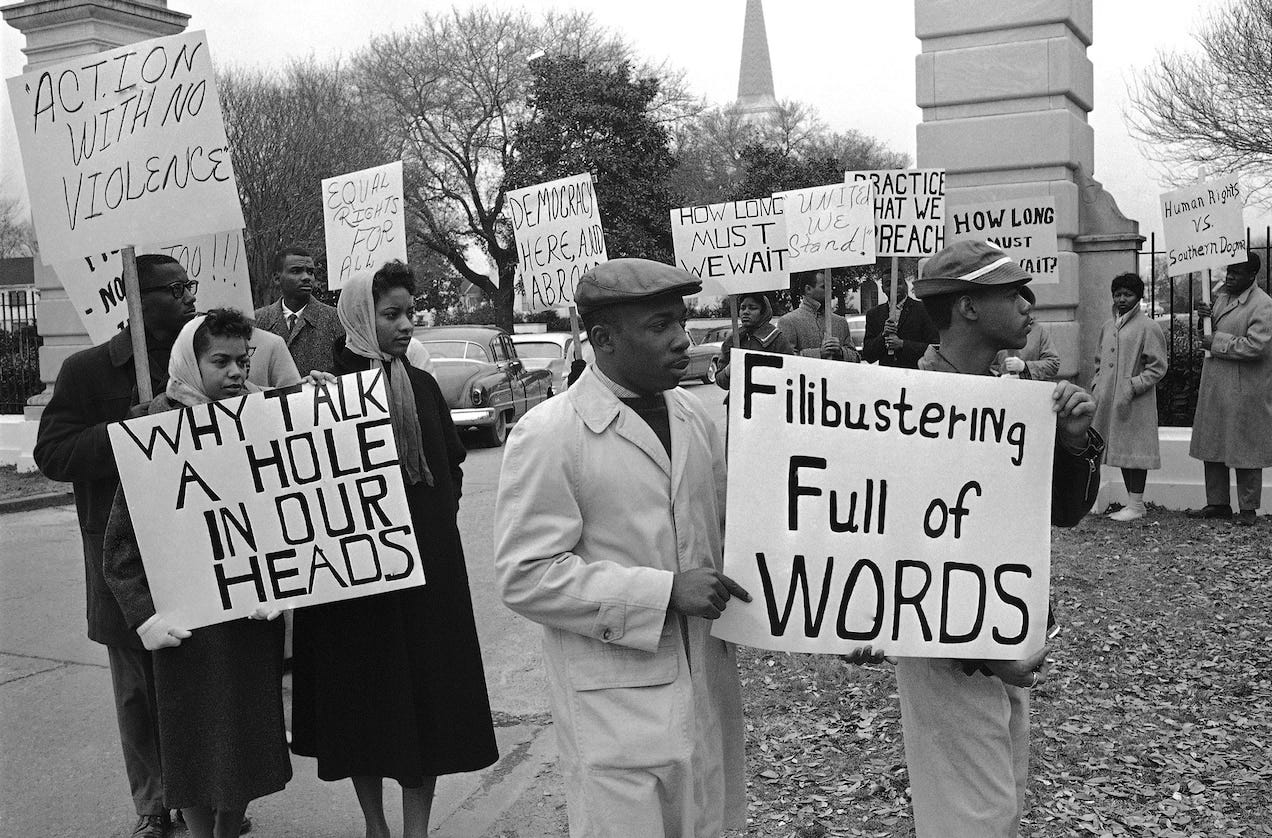

History bears this out. The most notorious uses of the filibuster occurred during the Civil Right Era, when Southern senators such as Strom Thurmond and Robert Byrd famously sought to block passage of civil rights legislation. They formed a minority faction strong enough to prevent cloture and then used it to maintain white supremacy during the Jim Crow era, including stopping bills that made lynching a federal crime and that would have outlawed the use of poll taxes which kept Black Americans from voting.

On March 9, 1964, when the landmark Civil Rights Act was sent to the Senate floor, Southern Democrats launched a filibuster to block the bill. The delay lasted a record 60 days, including Saturdays. It was a shameful and racist attempt to stop the legislation. On June 10, a coalition of 27 Republicans and 44 Democrats finally mustered enough votes to force cloture on debate. Prior to that date, no full-featured Civil Rights Act bill had ever survived a filibuster attempt on the Senate floor.

Senator Sinema is the first openly bisexual senator in our history, and her vote could prevent ongoing pernicious discrimination against millions in her own LGBTQ community. Senator Manchin, like his predecessor Robert Byrd, is a Southern Democrat in a deeply conservative state, and his vote could advance civil rights progress for millions of minorities, particularly African Americans blocked at the polls and systemically abused by the police. The quest for “bipartisanship,” on a matter as critical to our democracy as fundamental civil rights and civic participation, has always rested in the hands of too few—and always left too many behind for too long.

In light of the historic misuse of the filibuster to stall critical civil rights legislation, the filibuster rule should be interpreted today to not apply to laws whose specific intent is to expand the civic participation of traditionally underrepresented and oppressed minorities. This interpretation would not violate the pledge of Senators Manchin and Sinema to end the legislative filibuster, as it would still apply to every other kind of non-budgetary item. To tie this exception specifically to the Constitution, the rule interpretation could affect only those laws brought under the Elections Clause, the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, or the Equal Rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

In the words of Illinois Republican Everitt Dirksen, who finally mustered the Republican votes needed to end the Southern Democrat filibuster against the Civil Rights Act, “Stronger than all the armies is an idea whose time has come.” He continued, “The time has come for equality of opportunity in sharing in government, in education, and in employment. It will not be stayed or denied. It is here!”

That time is here again.

What a WONDERFUL idea! To the best of your knowledge, are any of our Senators who can propose something like this, aware of such a terrific, targeted compromise to get our government working for all of us again?