Congressional Redistricting Is Finally Done. But Where Does It Leave the Dems’ House Majority?

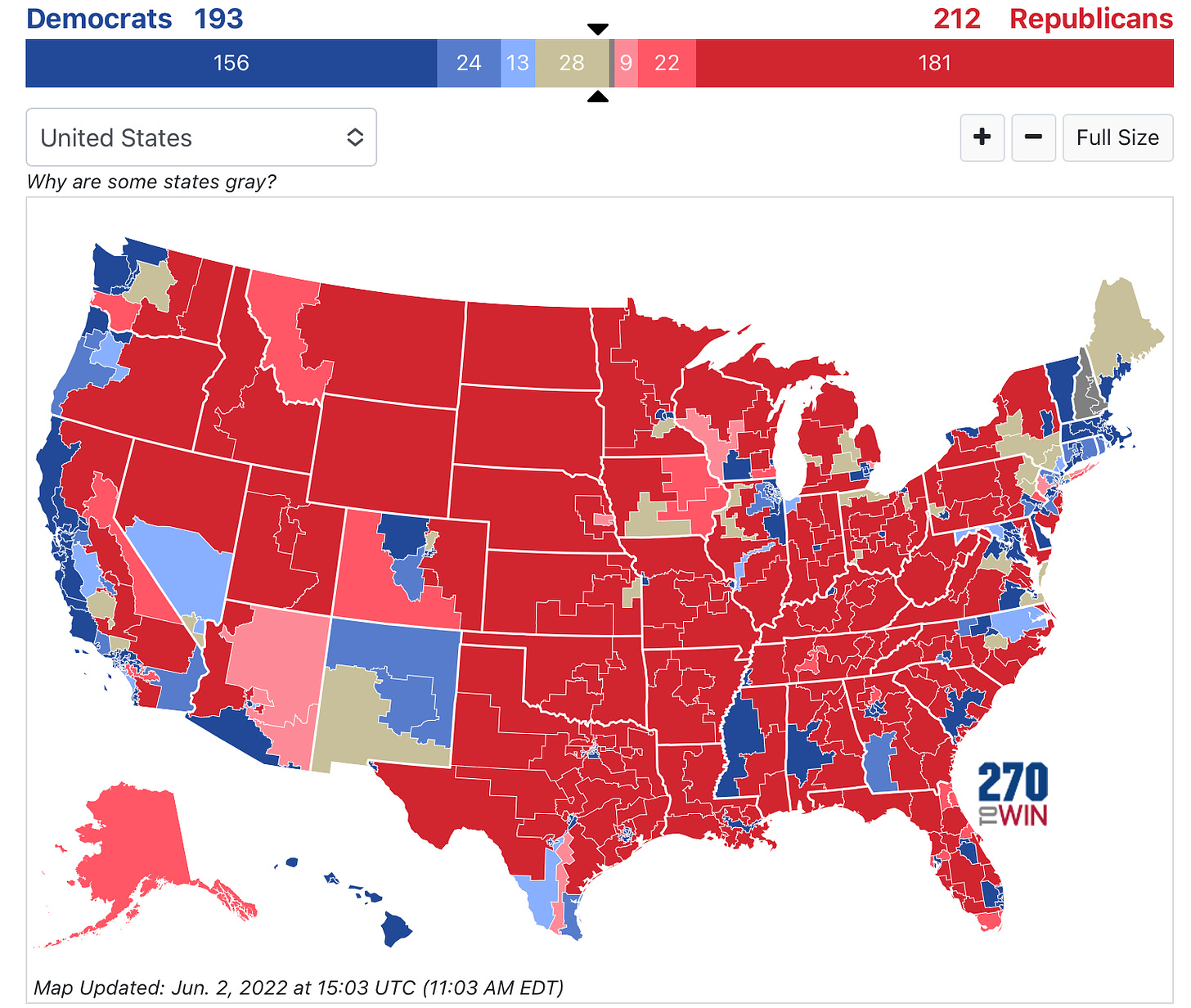

After a long year of legislative and court battles, and after state supreme courts in New Hampshire and Florida this week declined to consider challenges to the final district maps, the national congressional map for 2022 leaves the parties almost exactly where they began: with Republicans having around a 2 percent national tilt in their favor. This means Democrats theoretically would have to overperform nationally by that much to hold on to their slim majority in the House. That will prove a very tough bar in a midterm election where the president’s poll numbers are lagging.

Predictions for how the redistricting process would go swung dramatically over the past year. Before map redrawing began, it was widely assumed the GOP would use their control of state legislatures and state houses to press for even more egregious gerrymanders. The process began with Republicans fully controlling states where 187 districts would be drawn, while Democrats only controlled the map drawing process in states where 75 districts could be affected.

Then two things happened.

First, the GOP unexpectedly got cold feet after looking at the demographic trends in many of their existing districts. So instead of expanding their advantage, in states such as Texas the Republicans moved to cement their incumbents’ power—and as a consequence also made many Democratic districts even bluer. The result is that the number of theoretically competitive seats (i.e. won by a margin of 10 percentage points or less) has dropped from 89 to 76 nationwide, mostly because the GOP turned competitive districts into safe ones.

Second, the courts wound up helping Republicans in the final stretch. Where Democrats sought to use the same tactics the Republicans used back in 2012, with New York leading a charge to draw heavily favorable maps that could shift up to five seats their way, the state courts blocked their efforts and ordered the maps redrawn. Not so in Florida, however, where the extreme maps put forth by Gov. DeSantis, after he vetoed his own parties’ maps for being not aggressive enough, were left in place by the Republican controlled state supreme court even though a lower court said it illegally diluted the power of black voters by eliminating a long-held majority black district.

The result is that the pendulum swung right, then left, then wound up pretty much where things began. Unsurprisingly, both parties are now trying to spin this stalemate as a win.

Kelly Burton, president of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee Democrats, noted that the number of Congressional seats on the map for each party has moved their way. This is another way of saying that, based upon how people voted in 2020, there are now 226 Biden-won House seats to 209 Trump-won seats, a shift of +1 in the Democrats’ favor since 2020. More importantly, she stressed that the map is far better than it looked in 2012:

Significantly, the additional margin by which Democrats need to win the popular vote in order to win the House has drastically decreased compared to last decade - likely now closer to 2-2.5%, down from the 5-8% advantage Dems previously needed to secure a majority.

Republicans feel comfortable as well, however, with the results. “If we’re fighting to a draw on a map that everyone agrees is good for Republicans, that’s good for Republicans,” said Adam Kincaid, executive director of the National Republican Redistricting Trust. He has reason to feel optimistic: The non-partisan Cook Political Report currently gives Republicans a gain of 20-35 seats, far more than they need to take back control of the House.

It’s important to note that Democrats were at a structural disadvantage from the get-go because large blue states, such as California, Colorado and New Jersey, turned over redistricting to independent commissions. Further, state high courts in Democratic states like New York and Maryland held Democratic legislatures to account, pushing back effectively on bald, partisan gerrymanders. But this was less common in red states: Ohio, for example, also has a redistricting commission approved by its voters in a referendum, but it was controlled by GOP partisans whose maps were rejected repeatedly by the Ohio Supreme Court, which had no ability of its own to appoint a special master to redraw the maps.

Zooming out, Democrats did improve their chances considerably over the disastrous maps of 2012. But the slight two-percent structural advantage that still remains, added to the traditional loss of seats by the party in power during the midterms, likely spells trouble ahead. The slim Democratic House majority could theoretically hold, but only if Democratic voters and Democratic-leaning independents turn out this November as strongly as they did in 2020, especially in the 76 truly competitive swing districts around the country. It will be up to party leadership and grassroots organizers to make that happen.

This is all so stressful. Thank you for your balanced analysis.