Gag Me With An Order, Appellate Version

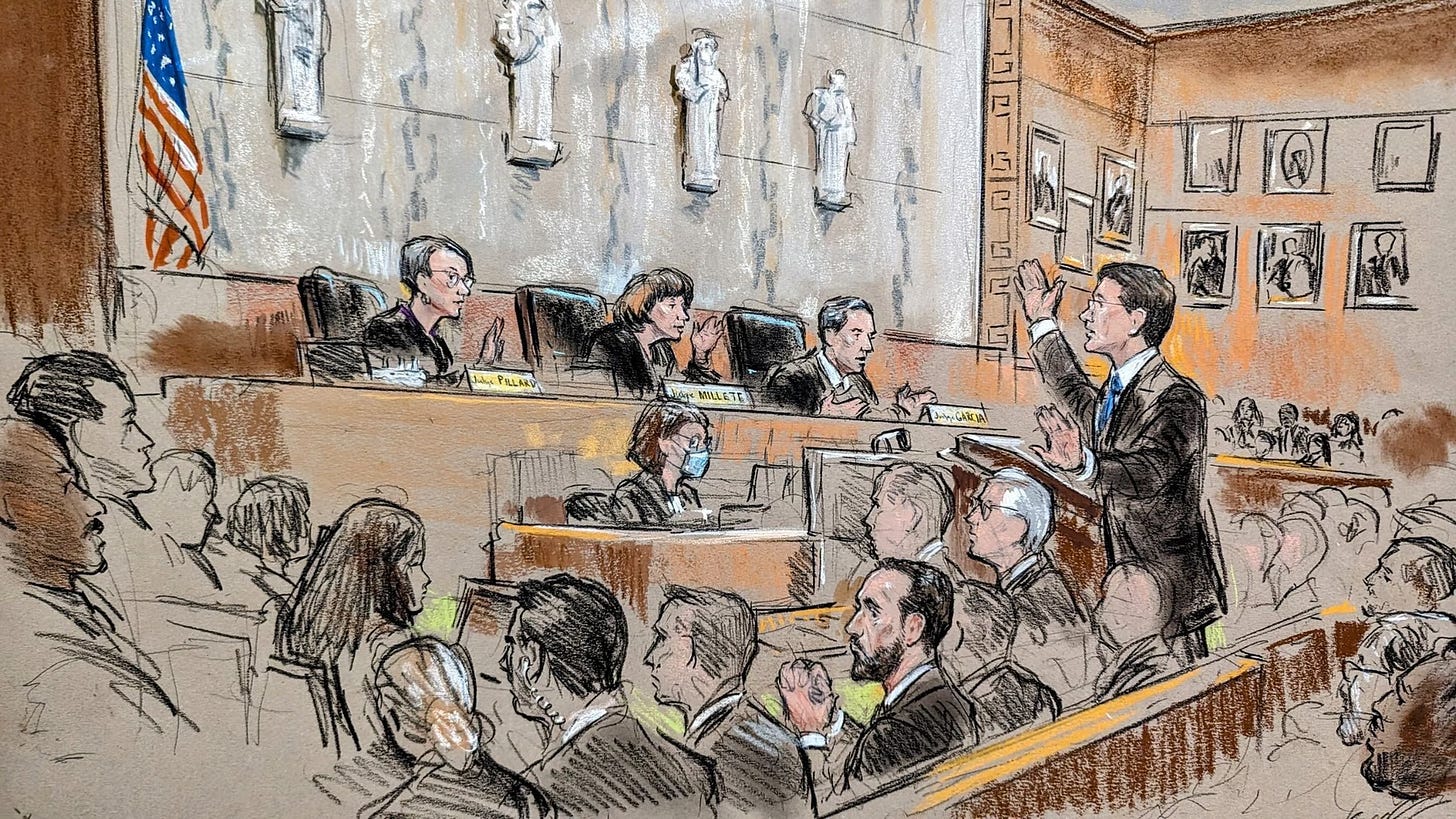

The D.C. Court of Appeals heard argument on Monday over Judge Tanya Chutkan’s Limited Protective Order against Trump

Trump’s legal team and the D.C. prosecutors were back in court on Monday, this time before a three-judge panel of the D.C. Court of Appeals. At issue was the protective order—known commonly as a gag order, though it is a limited one—that Judge Tanya Chutkan had placed upon Trump after his numerous public attacks and veiled (or sometimes unveiled) threats against witnesses, court personnel and the Biden Administration.

The panel heard a weighty and, until this case, never-before considered question: How far can a judge restrict the speech of a criminal defendant who is also a leading political candidate for office, in this case for the presidency itself? While courts have a duty to protect the orderly administration of justice—meaning they can’t allow things like witness intimidation, threats to court staff or the tainting of the jury pool—they must also respect the free speech values embodied in the First Amendment.

To complicate things further, political speech is among the kinds of speech most protected historically by the courts. And Trump is a master of saying things that he knows might cause others to act on his behalf, so it’s difficult to point to what he says and draw a straight line of causation from them to any harm to witnesses or the case.

During a lengthy oral argument, what Prof. Joyce Vance aptly calls a “hot bench,” the appellate panel pressed both sides on their positions. Trump’s lawyer, John Sauer, took an absolutist position, saying that no restrictions on his client’s political speech could be countenanced under the First Amendment. The judges seemed unimpressed by this and quickly cornered Sauer with several examples and hypotheticals that demonstrated how his argument was untenable.

When it was the prosecution’s turn in the barrel, however, the judges also posed tough questions. They asked the state’s lawyer, Cecil Vandevender, how a thick skinned prosecutor like Jack Smith could possibly be impacted by Trump’s near-daily missives and how they could cause any real prejudice to the case.

Let’s take a closer look at how the argument went. I’ll go out on a limb and venture that the gag order will remain in place, though it may be more limited in light of what we heard in oral argument.

But his free speech!

A gag order is preventative in nature. It’s intended to stop possible harm by limiting what a criminal defendant can say publicly about the case and witnesses. Judges have been imposing gag orders for decades without any party successfully raising serious First Amendment challenges, largely because it’s widely accepted that a criminal defendant who receives pre-trial release may forfeit certain speech rights in exchange for not being detained.

Trump in fact is subject to a pre-trial release agreement, and it requires him not to violate the law. That includes things like witness intimidation. So we would already seem to be in the realm of limitations on his speech, with the only questions being how many limitations and of what kind.

But you wouldn’t figure any of that listening to Trump’s lawyer Sauer argue. In his worldview, the former president should be permitted to make any statement he likes so long as his words did not create an “imminent threat” to witnesses, for example. This is the standard usually reserved for questions of incitement, where political speech may lose its First Amendment protections because the speaker created an imminent threat to public safety through inflammatory words. (It is no small matter, by the way, that a judge in Colorado on Friday found that Trump’s speech at the Ellipsis on January 6 in fact did incite insurrection and was not protected speech for this very reason.)

The problem with Sauer’s argument, as the judges quickly pointed out, was that it would require the government to refrain from acting preemptively to stop harm. If the panel were to adopt his reasoning, a court would have to wait until harm was actually demonstrated before it could issue a gag order, and by then the damage would have been done. Witnesses would feel scared and might not come forward. Court staff would feel intimidated. Justice would be undermined.

“Why does the district court have to wait and see, and wait for the threats to come, rather than taking reasonable action in advance?” Circuit Judge Brad Garcia asked Sauer.

The judges had reviewed the record carefully, and they knew that this wasn’t just some abstract question. Trump has demonstrated a long pattern of assailing his perceived enemies online and in speeches, leading to threats against them. This happened regularly as he pushed out the Big Lie, with election workers such as Ruby Freeman and officials such as Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers threatened for merely doing their jobs after Trump amplified their names to his base.

And it happened recently, too, even in this very case. After Trump posted the ominous words, “If you go after me, I’m coming after you” on his Truth Social platform, the very next day Judge Chutkan received a voicemail death threat filled with racist invective from a Trump supporter.

In another case, when Trump targeted the clerk of Judge Engoron in the New York civil fraud case as a “Democratic operative” and “Schumer’s girlfriend,” she immediately received threats as well. Judge Engoron imposed a limited gag order to protect his clerk, and that is also now on appeal with many of the same First Amendment issues.

Saeur relied heavily on a concept known as the “heckler’s veto.” This is from a Supreme Court case decades ago known as Tinker, where the Court held that the government could not restrict the free speech rights of a speaker unless the speech causes, or threatens to cause, a substantial disruption or infringes on the rights of others. In other words, the government is generally prohibited from restricting speech solely based on the disruptive or violent reaction of the listeners or onlookers (here, the heckler).

In this case, Saeur argued that the court is facing a heckler’s veto scenario. The trial court is seeking to restrict Trump’s speech based on the assumed disruptive or even violent reaction of his base.

But it’s not a great analogy. In the heckler’s veto situation, disruption results from others being antagonized by what they hear. They take action to try to shut the speaker down. Trump’s case is different because he is deliberately trying to leverage the anger and violence of his base to silence the speech rights of others.

“I can’t help what other people do” doesn’t work as a heckler’s veto argument if those people are your followers and they are hanging on your every word. You very much can help what they do, for example by not riling them up in the first place against witnesses.

But what about his political campaigning?

The panel also seemed to recognize that Trump is not like other criminal defendants in one key way: He is the leader of the party currently largely out of power, and therefore nearly everything he says has some protection as political speech.

It’s often difficult for opponents of Trump to see any value in his speech, especially when it simply feels like nonstop insults and whining. As a thought experiment, it’s helpful to imagine a situation where the shoe is on the other foot.

Suppose that Trump wins the election in 2024. (I know, but bear with me.) He keeps himself out of prison by executive order and through a compliant Attorney General, Stephen Miller, then as promised goes after his political opponents.

Miller’s Justice Department obtains indictments against his political opponents, including fraud charges against Pete Buttigieg, who has declared himself a candidate in 2028 to defeat Trump. Buttigieg goes on the offensive and condemns the indictment as politically motivated, says that charges against him were trumped up by a corrupt DoJ led by Miller, and that the so-called “witnesses” against him like Kash Patel, Marjorie Taylor Greene and Steve Bannon are liars and sycophants who have fabricated evidence and will say anything to please their master.

The Justice Department, its case against Buttigieg now pending before Judge Aileen Cannon, moves for a broad gag order, claiming that Buttigieg is riling up the leftists to attack Patel l, Greene and Bannon, who have indeed received death threats. They want to muzzle Buttigieg from saying anything at all about his case or the witnesses, or even against Special Prosecutor Elise Stefanik, who has brought several cases against Trump’s rivals to pin them down.

In such a nightmare scenario, we would want Buttigieg to have as broad a right as possible to attack the credibility of these witnesses and to assail the injustice of the proceedings against him. After all, he’s the leading presidential candidate and is beloved by his base of supporters, who have put all their hopes in him to rid themselves of the autocrat in the White House.

Now that I’m done scaring you, I hope you can see how courts have to craft rules around gag orders that take into account the fraught political realities of our time, and not just to silence Trump for being Trump. Somewhere there is a line between allowing politicians a pulpit to attack their political enemies without crossing over into the realm of witness intimidation through the leveraging of an impassioned or even violent base. (My apologies to Secretary Buttigieg for bringing him into this thought exercise.)

The panelists on the D.C. Court of Appeals seemed to hint that Judge Chutkan’s order may have overstepped, particularly on the question of Trump’s right to attack the Special Counsel, who unlike the witnesses is seasoned and presumably can handle himself against the sneers and taunts of the former president.

At the same time, the panelists realize that Trump is very deliberately inciting his followers because he has much to gain from it, including pressure upon witnesses who also happen to be his political enemies. These include high ranking officials during the Trump administration such as Gen. Mark Milley (whom Trump said should be executed for treason) and former Attorney General Bill Barr, who has come out strongly against Trump since leaving office. How should they handle Trump’s political attacks upon people who openly and regularly criticize him? It might seem unfair, and as “election interference” by his base, if the courts permitted their attacks on Trump to continue but prevented him from responding.

Whatever the result, which I believe will be a reimposition of the gag order but with some tweaking, Trump will likely appeal further, either to the entire D.C. Circuit for en banc review or to the U.S. Supreme Court. Some kind of standard for how judges should handle gag orders in the case of protected political speech must be developed, and that kind of thing generally only comes from the highest court given the stakes.

By the way, if you never want to see the likes of Elise Stefanik as Special Counsel prosecuting Trump’s political enemies, please make a plan now to organize, donate generously and vote. It’s all on the line in 2024.

The only problem with your thought experiment is this: we may extend the courtesy of narrowing trumps gag order to exclude political speech, another Trump administration that includes Miller and Stefanik, would not, and would have no problem with the optics of a total gag on Sec. Butiegeig. In fact, they would revoke his pre-trial freedoms. Trust people when they tell you who they are.

The issue I have with the question of lifting the gag order--even in your thought experiment--is that elements of the case must remain within the confines of the court proceedings. TFG can currently spout ludicrous attacks on witnesses and court staff under the guise of "free speech", but the witnesses and staff aren't afforded their right to cross-examine or otherwise defend themselves. I also fail to see how "Gen Milley should be shot" or "the court clerk is Sen Schumer's girlfriend" are considered "political speech".