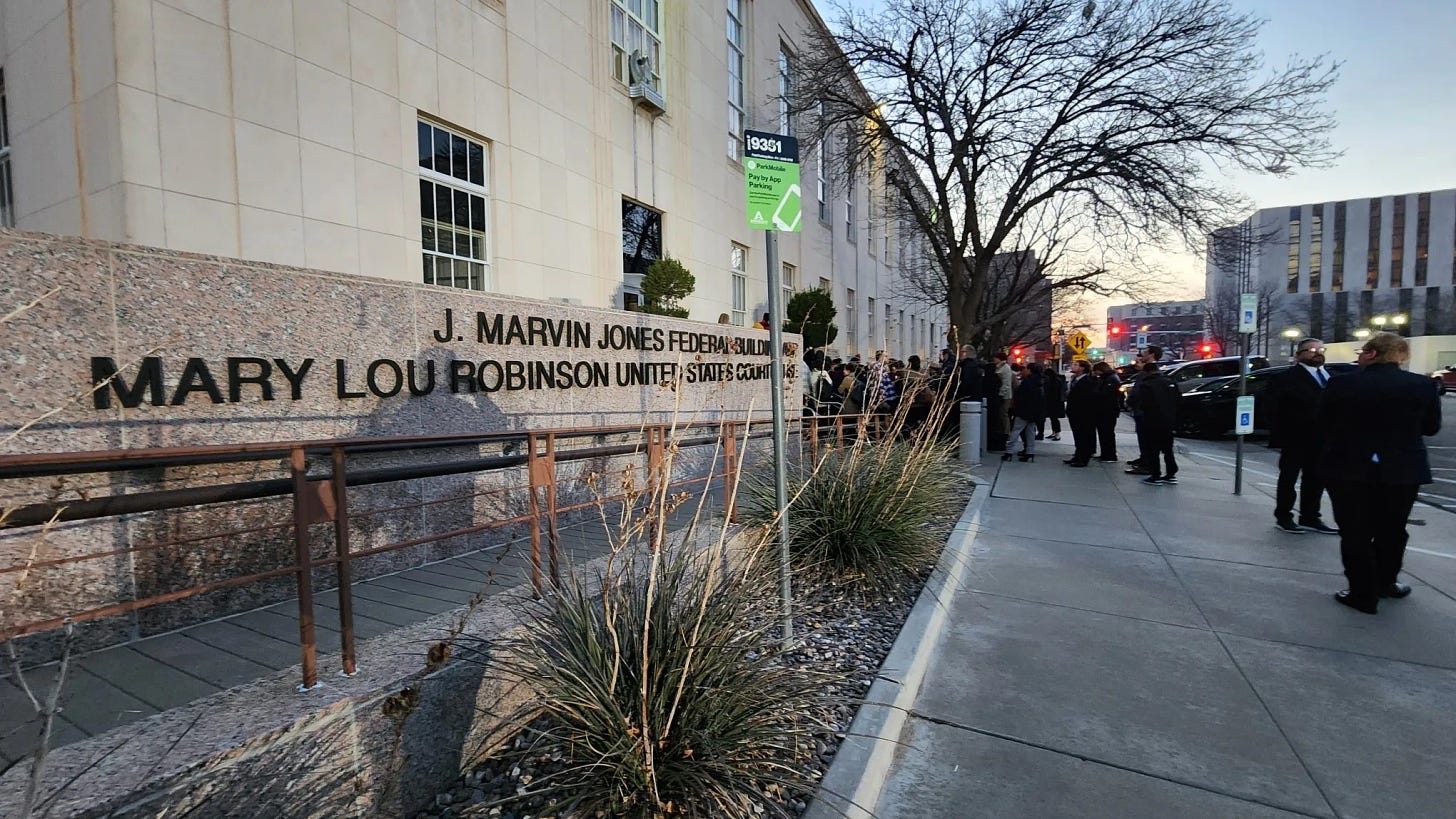

There was a four hour hearing in Amarillo, Texas, yesterday in a case that very likely will have national repercussions for abortion access for millions. The plaintiffs, a group of anti-abortion activists, are trying to halt the use of mifepristone, which blocks the hormone progesterone and is commonly used with another drug in combination to end pregnancies within the first 10 weeks. The plaintiffs want the district court to order the FDA to suspend or withdraw its approval for the drug, which has been safely prescribed for two decades and is used in around half of abortions nationwide.

The case landed in Amarillo by design. U.S. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, a Trump appointee, is one of the most radical-right jurists in the country, and the appellate court that sits above him, the Fifth Circuit, is one of the most extreme and conservative.

Based on arguments and questions from the bench during the hearing yesterday, there is strong reason to believe Judge Kacsmaryk will indeed issue some kind of ruling blocking mifepristone nationwide, sparking a crisis over access to medical abortion drugs, even in the blue states where abortion is legal and protected.

This situation raises a number of important questions, so I’ll try to lump them into a few broad categories:

Can one judge in Texas really do that?

What possible legal grounds could there be for it?

What happens after such a ruling?

Are there defects to the plaintiffs’ case on appeal?

Let’s take these one by one.

Can one judge in Texas really do that?

The short answer is yes. Any federal judge has the power to issue an injunction, which is a fancy word for a court order to a party to halt its behavior or to compel it to act a certain way. A federal court can issue an injunction against an agency of the government or even the entire U.S. government. This is usually a good thing to keep as a backstop against executive power. If you remember back to the Trump era, a single judge initially blocked his entire Muslim ban with an injunction.

That’s precisely why the plaintiffs, who are anti-abortion activist organizations and doctors, maneuvered to get their case in front of Judge Kacsmaryk, a former attorney for a Christian legal group who is known for his staunchly anti-abortion views. He’s also the sole district judge in the region, and as a result his court receives all new cases filed there.

This practice of picking a place to file because you like the judge is called “forum shopping,” and it is both highly criticized and often used, as Trump’s federal civil lawsuit to get the Mar-a-Lago classified documents case before sycophant Judge Aileen Cannon recently demonstrated. Judge Kacsmaryk’s docket has filled up with conservative-led cases precisely because many on the right deem him sympathetic to their causes.

Judge Kacsmaryk had said during his contentious Senate confirmation hearing that it would be “inappropriate” for a judge to allow religious beliefs to impact a matter of law and pledged to “faithfully apply all Supreme Court precedent.” But since being seated, his rulings have directly attacked birth control access, the Affordable Care Act, and Biden’s border policies—all darling causes of the right. Now it’s his big chance to take on abortion on a national scale, and it seems he’s entirely willing to do what he was picked to do.

What possible legal grounds could there be to order a halt to the use of the drug?

At the hearing, Judge Kacsmaryk seemed to zero in on two arguments put forth by the plaintiffs to try to show the FDA had approved the drug unlawfully.

First, the plaintiffs asserted, contrary to the factual record, the conditions in the studies on which the FDA relied did not match the conditions under which it later permitted the drug to be administered. It was “apples to oranges,” they claimed, a phrase the judge came back to with favor. Specifically, plaintiffs alleged that while the FDA’s studies all featured patients who had received ultrasounds before being treated with the drug, that condition wasn’t among the requirements to prescribe it.

The government responded that the law gives the FDA, and not a court, the discretion to determine which studies were adequate to approve a drug as safe. This is a strong argument, because courts don’t have the expertise to be making such decisions or second-guessing the science. Moreover, the FDA had in fact looked at studies where patients didn’t receive an ultrasound, so plaintiffs were simply incorrect in claiming it was “apples to oranges.”

Second, the plaintiffs contended that the FDA had improperly accelerated the process for approval of the drug, an argument the judge appeared to buy. Seeming to do the work of the plaintiffs for them, Judge Kacsmaryk remarkably informed the government during the hearing that he personally had downloaded a list of other drugs the FDA had approved through that process, which were mostly treatments for HIV and cancer. He then proceeded to ask the government for its “best argument” for why mifepristone should fit into that list.

But the “accelerated approval” argument raised by plaintiffs was also factually incorrect, rendering this line of questioning by the judge completely off-base. As Senior Writer for Slate, Mark Joseph Stern noted, the FDA took four years to approve mifepristone. It was not an accelerated approval at all. The approval occurred under a subpart of the regulation that imposed restrictions on the drug’s distribution. But that subpart’s title of “accelerated approval” applied to restrictions on the drug, not the approval of the drug itself. So what actually got accelerated was the process to approve extra restrictions—something about which the plaintiffs ought to have been happy. By implying that the drug approval itself was accelerated, plaintiffs are trying to pull a fast one, and it unfortunately looks like Judge Kacsmaryk accepted it, either because he wanted to or he doesn’t understand the distinction.

What happens after such a ruling?

Assuming Judge Kacsmaryk issues some kind of injunction against the FDA, either by deeming the entire approval unlawful or “drawing lines” around certain later regulations of the drug and enjoining those, an important question is whether he will stay his ruling pending appeal, meaning keep it from going into effect until a higher court has had a chance to rule on his injunction. Such a stay from the court is unlikely, given that it appears Judge Kacsmaryk really wants to strike a real blow to abortion access from his bench. The government is already readying its response, both legally and in practical terms, to any injunction that halts the use of the drug. (For example, on the practical side of things, the FDA has noted that there are other medications that could be used in place of mifepristone, though they are not as efficacious or free of side effects.)

If there is no stay from the district court, then the government can move immediately for an emergency stay before the Fifth Circuit. A lot will depend on which panel of jurists gets picked to hear the emergency appeal. But I wouldn’t count on the Fifth Circuit doing the right thing. After all, the last time an important abortion decision came down permitting Texas’s blatantly unconstitutional vigilante-enforced abortion system to remain in place, the Fifth Circuit (and later the Supreme Court) refused to stay the effect of the order pending appeal. That effectively meant most abortions became illegal in Texas long before the Dobbs decision even came down.

And this is what has me most concerned. As Ian Millhiser, Senior Correspondent for Vox, noted, the appellate courts, including our highest court, can simply leave the status quo in place while a case slowly winds its way through the system. When that status quo gets to be set by an extremist judge, it effectively leaves a harm in place that could take years to undo, if ever.

Still, there’s a chance that if SCOTUS winds up with the case before it, as is ultimately expected, it could grant a stay without having to reach the question of whether the FDA used an unlawful approval process twenty years ago, a question which would open a huge can of worms. I explain the reasons for this below.

Are there fatal defects to the plaintiffs’ case on appeal?

The statute of limitations. One of the problems plaintiffs have is that the FDA’s approval took place back in 2000, meaning that more than two decades have passed without the plaintiffs taking any action to stop mifepristone on grounds that the original approval was unlawful. That presents a threshold question of whether the plaintiffs filed their case far too late, meaning beyond the six year statute of limitations.

If you challenge an agency action, you generally have to exhaust what’s called your “administrative remedies” before filing a court case. The FDA regulations specifically require “citizen petitions” before any legal action can be filed in federal court. Here, there was a citizens petition filed by the plaintiffs in 2019 to undo a 2016 revision to the regulations on the administration of mifepristone. But that petition didn’t cover the 2000 approval itself. The plaintiffs argue that the time clock “resets” every time the FDA made a modification on the drug’s restrictions. But the government counters that, even if that were true (which it isn’t), anything not in the 2019 petition, including the original 2000 approval, is now clearly barred by the statute of limitations.

Standing. There’s also the question of whether plaintiffs here have the proper standing to sue, meaning whether they were actually harmed by the actions of the FDA. A case where the plaintiffs lack standing can and should get booted out the gate.

The plaintiff organizations claim they have members within the jurisdiction in Texas who were harmed because they will have to treat patients with complications from mifepristone and therefore would have less time and resources to treat other patients. There are also three individual doctors suing who are making this claim. The government argues that this harm is speculative and could open the door to any doctor challenging the FDA’s approval of any drug on grounds it takes away from time to treat others.

In both of these cases, it would seem the government has the better argument, but whether it will be enough for the appellate courts to turn back the activist district court remains to be seen.

Activist courts require activist response

For decades, conservatives on the right have decried “activist judges” who, they claim, impose their values on society on things like gay rights, abortion, and the separation of church and state. Today, it seems clear, the shoe is on the other foot. There are now activist conservative federal district court judges willing to strike down abortion access for millions of women; activist conservative appellate judges who are imposing their views on matters from gun safety to vigilante justice; and an activist conservative majority on the Supreme Court willing to overturn five decades of precedent and return us to the “traditional” values of 17th century America.

Courts can inflict a lot of damage by undoing protections and rights enjoyed by the citizenry. But when they fall too far out of step with public opinion, they lose the only real power they have: their legitimacy. After all, courts don’t have control over armies or vast treasuries like the executive and legislative branches do. Ultimately, they are only as powerful as the people agree they should be. Chief Justice John Roberts may have arrived at this realization too late, as he now witnesses the effects of his earlier opinions giving corporations unfettered rights to flood our system with corrupting money and gutting the protections of the Voting Rights Act.

The answer to such blatant disregard for the welfare and rights of the vast majority of the public is for that same public to impose controls and reforms upon the courts, from term limits to increased judicial panel sizes. But this can only be achieved if the public elects a Congress and a president willing to take steps to protect liberal, democratic values. We are tantalizingly close to such a majority: In the last election, we fell five votes shy in the House and one vote shy in the Senate of having 50 votes to reform the filibuster, which is blocking bills addressing voting rights, abortion rights, and judicial reform.

The 2024 election looms large in many senses as a result. It is our best chance not only to turn back the anti-democratic extremism of the GOP but also to put a check upon the power of right-wing courts to wreak further havoc on our rights and liberties. The mifepristone decision, due out soon and likely to send shockwaves through the country, should serve as another rallying cry for everyone who values reproductive rights and personal autonomy.

The courts on the far right are unquestionably activist. And so, in response, we must all become citizen activists.

Yes yes yes we must all become citizen activists! This is exactly right. There can be no sitting on the sidelines at a moment when our basic rights are under attack. If you need guidance about how to *get* active there are many of us who can help you. But it's time for everyone to use your voices!

Please reconsider your use of the label “Conservative”. The political party calling themselves Republican are no longer a party that honors conservative values. They are acting as reactionary radicals. Using the appropriate labels can help frame the situation better.