It has long been an ambition of mine to visit South Africa, not just for the wondrous and unique landscapes and the opportunity to go on a safari, but for the chance to witness the transformation of a country once under the dark shadow of institutionalized racism.

In many ways, South Africa in the 20th century was what the entire U.S. might have become, had the South prevailed in our own civil war. Apartheid was, as many historians note, the full embodiment of the Jim Crow South. White South African leaders even visited America and came back excited about the prospect of importing and expanding upon Southern segregationist policies. They wondered, how had an entire region in the U.S. managed to subjugate its Black population so entirely and “legally”? Apartheid was South Africa’s uniquely brutal response, and its consequences were devastating for millions living under it.

My sister Mimi and I prepared and planned a trip to Cape Town that would allow us time to explore this history. On Wednesday, we seized a unique opportunity to visit Robben Island, where South African leader Nelson Mandela had been incarcerated for some 18 years, and later that day to attend a walking “freedom” tour that highlighted some of the story, and the excesses of, apartheid.

As our guides explained, apartheid was more than a system that kept the various races physically apart in South Africa. Under the extremist, racist laws passed by the far-right Nationalist Party after it took power in 1948, non-whites were stripped of rights to enjoy full personhood, to vote, to travel, to work, to be educated, and to use public facilities, just to name a few.

People of African descent were forced into substandard primary schools and could not become degreed professionals, other than as doctors or lawyers. And even then, they could only have Black clients. Nelson Mandela, after becoming a lawyer, was required to use white proxy lawyers to provide services to his white clients so as not to run afoul of the apartheid laws.

The different races not only could not intermarry, they could not even have sexual relations with one another. Our Freedom Walk tour guide noted that the state often monitored the sexual activity of suspected transgressors—a hallmark of fascist regimes. Comedian Trevor Noah, who hails from South Africa, wrote an autobiography entitled “Born a Crime” because his very existence, born to a white Swiss father and a Xhosa mother, was evidence that his parents had violated the law.

Our walking tour guide was born a white South African, but is now in his late 20s and stands firmly on the side of progress and racial equality. Along our walk, he took us to see this building, The High Court Civil Annex.

Within these rooms and hallways, the government rendered decisions relating to the race of petitioners who came before it. At the top of the system were the whites of European descent, followed by East Asians and Indians in the second group, then the “coloureds” of mixed ancestry, and then the Africans, sometimes referred to merely as “African” or the catch-all but culturally meaningless term “bantu.” Blacks comprised around 85 percent of the country at the time, but legally occupied just 7 percent of the land.

Determining race was a tricky thing sometimes for these officials in the High Court Civil Annex, who devised an infamous 200-factor test to decide whether someone who was “trying for white” could be granted that coveted status. One of these factors, which was widely mocked as demonstrating the insane excesses of the racial purists, was the so-called “pencil test.” The questioner would take a pencil and place it in the applicant’s hair then have them shake their head hard three times to see if the pencil stayed in place. The belief was that white hair would let it fall but African hair would not. When our guide told this story, I couldn’t help but exclaim, “No! You’re making this up!” But he was quite serious.

Besides borrowing segregation from our Jim Crow South, there was another striking and worrisome parallel: The Nationalist Party and its allies won the election of 1948, in which only white citizens could vote, by just five seats in parliament, a count of 79 to 74 seats over the opposition. The Nationalists had actually failed to win the popular vote, even after running on a disgraceful campaign of fear, often citing the “Black Peril” to drive white anxiety. Despite the lack of any popular mandate, they moved to implement the core racist laws that later became the foundation of the apartheid system.

America stands on a similar precipice today, with a political minority of white, Christian extremists close to control of our entire nation.

One of the most hated tools of the apartheid system was the so-called “Dom pass.” Our guide on Robben Island, pictured below, held up a copy of her grandfather’s pass book. Every person in South Africa had to possess papers showing their identity, race and where they lived. But only non-whites had to carry the Dom pass at all times. It acted like a passport or visa, as if they were visiting a foreign country even when within their own country’s borders. Failure to carry the Dom pass and to present it on demand meant jail time, something that would also be recorded in your book. Our guide’s grandfather had been arrested and jailed several times for failing to carry or present his pass book on demand.

Nelson Mandela helped lead a nationwide protest against the Dom pass system. Under the auspices of the African National Congress, Mandela organized a mass burning of pass books, which landed any who participated in jail. Mandela himself, and later his wife Winnie, were often banned from traveling to certain parts of the country, and violations of the ban resulted in detention and jail for them.

As a younger man, Mandela espoused strict non-violent resistance to apartheid. One of the ANC’s strategies was to have protestors intentionally break the laws regarding separate public facilities, in much the way Blacks fighting segregation in the U.S. sat at whites-only lunch counters. But at one demonstration, at the police station at a town called Sharpeville, the authorities turned their guns upon the protestors and fired indiscriminately. There were 269 victims that day of March 20, 1960, including 29 children. In all, 69 people were killed and another 180 injured. Many were shot in the back as they tried to flee.

That incident drew worldwide attention to and condemnation upon South Africa and its apartheid system. There were also protests, strikes and riots around the country following the massacre. Rather than loosen its apartheid laws, however, the hard-right National Party doubled down, declaring martial law and granting police arbitrary detention powers for up to 90 days. Activists were rounded up, beaten, tortured and disappeared for months without trial or charge. The ANC was banned as an illegal organization.

This led Mandela to conclude that non-violence was not, on its own, ever going to force the government to change its policies and liberate the country’s non-whites from under apartheid’s yoke. He went underground as he began planning and conducting sabotage of the nation’s infrastructure, all in a desperate attempt to grind the country to a halt economically. For a time he was known as the “Black Pimpernel,” a nod to a shadowy figure during French Revolution who held others escape the Terror.

Mandela now saw himself as a “freedom fighter” in charge of establishing a military wing of the ANC. He even went abroad to obtain training in guerrilla warfare and sabotage. But on his return to South Africa, he was captured by the authorities and incarcerated for leaving the country without permission. During his imprisonment, the leaders of the military wing of the ANC were captured in a raid that also unearthed evidence of plans by the leadership to conduct sabotage and possibly escalate to guerrilla warfare. All of the leaders, including Mandela who was already in prison, were charged with treason—a potentially capital offense.

At their trial for high treason, and faced with the possibility of the gallows, Mandela spoke in the group’s defense—a speech that lasted four hours and was reprinted in newspapers across South Africa and the world. At the end, Mandela pledged that the cause of freedom for Africans and an end to the oppression of apartheid was a cause for which he was willing to die.

Putting Mandela to death would have set the country on fire, and the judge knew it. Instead, he sentenced the arrested ANC members, including Mandela, to life in prison, to be served on Robben Island, where my sister and I visited on Wednesday.

Mandela was held in this cell, which was too small for him to fit lengthwise, given he was around 6’4” in height.

All of the prisoners slept on mats and were given threadbare, ratty blankets, far too thin to ward off the cold winter nights. During the daytime, at least for the first years, they endured hard labor in the open prison areas, breaking down rock into small shards by hand for hours on end. Later, they were ordered to the quarries on the island to excavate limestone. It was backbreaking work, with little but thin white shirts to shield them from the hot sun or the punishing elements.

Mandela’s ability as a prisoner to fight for justice and rights for his fellow prisoners on Robben Island was remarkable, even in the face of sadistic, racist guards and wardens who relished punishing the political prisoners for the tiniest of infractions. His ability not to lose hope, and to survive for 18 years there with only occasional permitted visits from his beloved wife Winnie, is eloquently recounted in his autobiography, “The Long Walk to Freedom,” which I read most of while traveling to and within South Africa. He penned most of that diary from within the walls of his prison, managing to create an opus while keeping its existence secret from his captors and tormentors.

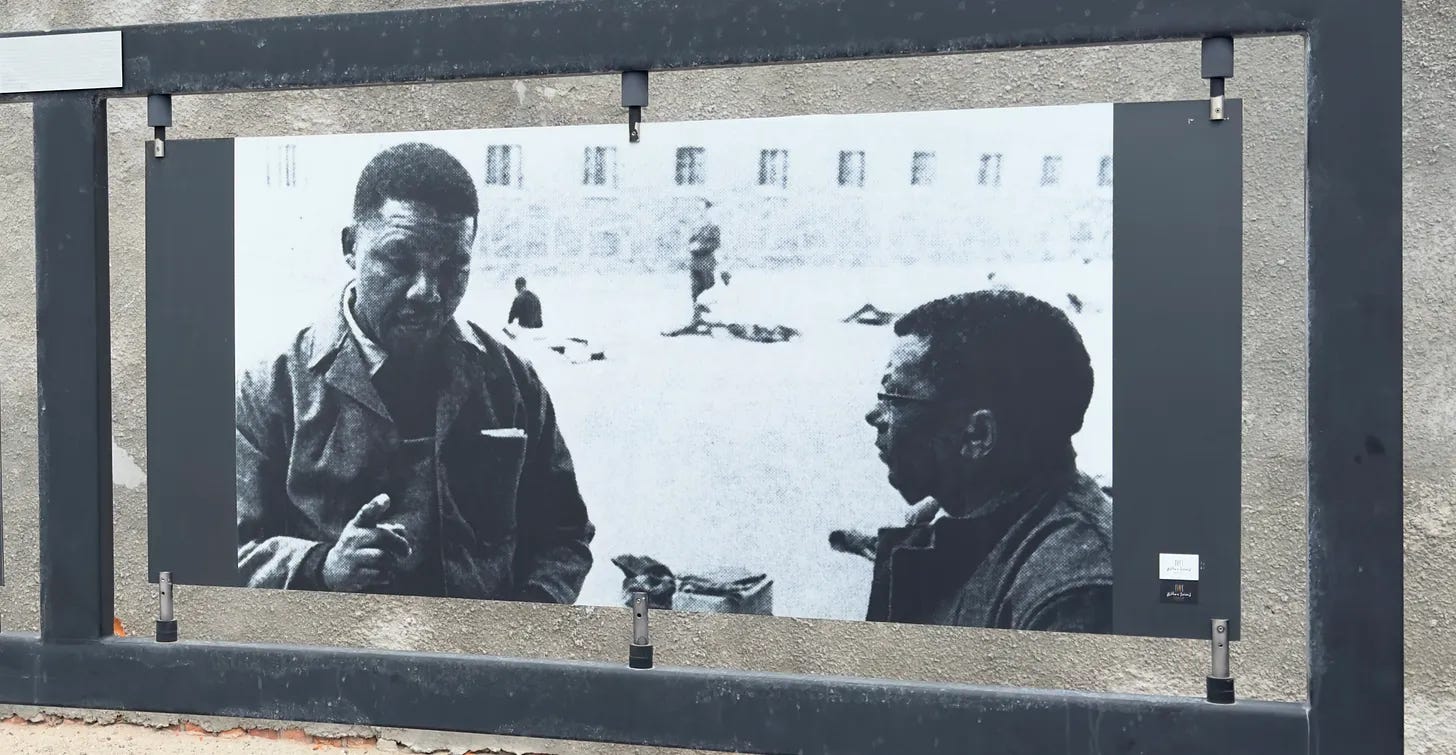

Here is the only known picture taken of Mandela inside Robben Island maximum security prison.

While Mandela was incarcerated, it fell to leaders on the outside to carry on the work of liberation. On our walking tour, we visited the Anglican Church in Cape Town where Nobel Prize winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu held his famous and inspired services.

The church was one of the few places where people of all races could gather in one location, without physical separation and momentarily free from the reach of the laws. One of the sole exceptions to the prohibition against any large public gatherings was for religious services. Tutu used that loophole to preach a message of hope and love, and to keep the outside world apprised of the horrors of apartheid.

(Our guide, who is the child of two lesbian mothers, gives great credit to Archbishop Tutu for insisting upon adding LGBTQ+ equality expressly into the nation’s new constitution—the first nation in the world to do so. After all, Tutu reasoned, if you get to start from scratch, you might as well include all of the rainbow.)

We also visited a piece of the Berlin Wall, presented by German Chancellor Helmut Kohl to Tutu during his visit to the country. The wall fragment symbolized another kind of enforced division—that between East and West Germany during the Cold War. But, as our guide explained, the fall of the Berlin Wall also held a direct connection to the fall of apartheid, something I wasn’t aware of until our walking tour.

South Africa’s Prime Minister at the time, F. W. de Klerk, had quietly decided to end apartheid, fearful that growing racial tension would lead the country into civil war. De Klerk gambled that with the fall of the Soviet Union, the ANC, which had many communist party members and strong ties to socialist regimes, would be friendless and therefore less able to organize, even if Nelson Mandela were released from captivity early. So he gave the order for Mandela’s release.

Mandela would not serve out his life sentence after all. Instead, he would work for four years to steer the country toward free and democratic elections. When he emerged from captivity, he went to the limestone quarries on Robben Island where he had done hard labor for years. There, according to our guide, he gave a speech before throngs of reporters, with many of his fellow prisoners, now freed men, beside him.

At the speech’s end, he did something unexpected but deeply symbolic. He picked up a single stone and placed it on the ground with great deliberation. Other prisoners took up the act, and soon a pile of rocks formed. It represented all their toil and suffering, all their long years together as friends and fellow freedom fighters on Robben Island. It still stands there today.

Mandela gave his first speech to the nation as a newly free man from the balcony of City Hall. A friend of our guide said that while he is not religious, that was the closest thing to a religious experience he had ever witnessed. Mandela stood on a balcony to address the crowd, but there’s actually a higher balcony, one level up, where he could have stood and commanded the attention of the more than 100,000 people who had gathered to hear him. But he chose the lower one deliberately to signal that he was a man of the people, not one who stood far above them like a king. A statue of Mandela now stands permanently at that location.

Our guide did not know whether the South African experiment of a multi-racial democracy would stand the test of partisan politics, yawning wealth inequality, and the continued pain and bitterness from the apartheid years. In this I share some of his hopes and concerns, reflecting on my own country years after we had also elected our first ever Black president.

It was oddly comforting to realize that South Africa had been through so much, and seen far worse racial strife and systemic white supremacy, than the U.S. had in the 20th century, and yet the torch that was lit for justice, freedom and democracy in that nation still burns with hope and promise. Mandela’s long walk is now over for him and his generation of freedom fighters. But the rest of us shuffle onward, his inspired words a forward drumbeat in our ears:

“What counts in life is not the mere fact that we have lived. It is what difference we have made to the lives of others.”

That's one helluva travel log. Beautifully written, thanks!

Thank you Jay, for so eloquently sharing your experience. I'm from Cape Town and was in elementary school when Nelson Mandela was released. I remember it well, the sense that our parents were holding their breaths and waiting to see what would happen next is engraved in my memory. Thank you also for drawing the parallels with what has and is happening in the USA (a place I now call home). Living here with the perspective of apartheid and post-apartheid as my backdrop has been intensely frustrating at times. Why are we so unable/resistant to learn from history? Enjoy the rest of your trip. South Africa is an incredible country and I'm fiercely proud to be a South African.