For two hours yesterday, the Supreme Court wrestled with the subject of gun regulation, something it hadn’t done since the Heller decision in 2008. That decision had affirmed the right of private citizens to possess a handgun in their home. But it also affirmed the right of state and local governments to pass certain gun-control measures, such as forbidding firearms possession by felons or the mentally ill.

Before the Court yesterday was New York State Rifle & Pistol Assoc. v. Bruen, which brought a challenge to a 108-year old New York law requiring persons wishing to carry a concealed handgun outside of their home to show “proper cause” for the issuance of the license. New York courts have held that to satisfy this, applicants must show a special need to protect themselves, rather than a generalized desire to protect life or property.

The Rifle & Pistol Association’s lawyer, Paul Clement, argued that the Second Amendment gives citizens a fundamental right to carry a gun outside of a home, and that the whole point of a right is that you shouldn’t have to gain pre-approval from a government official to exercise it. He said that the history of interpretation of the Second Amendment through the 19th Century supported his argument, and that the stringency of the New York law went too far.

The liberal justices—Kagan, Sotomayor and Breyer—pushed back. Kagan wondered, why stop at the 19th Century when interpreting the Second Amendment? The modern limitations on felons and the mentally ill possessing firearms dates back to the 1920s and have been upheld since. Sotomayor cited a “plethora of regimes” that legislatures have chosen, from restrictive to permissive, from English law to the colonies to today, and said she wasn’t sure how the Court could simply ignore that history. Seeking a way out of what looked like a conservative victory, the liberal justices also pressed for more factual findings around exactly how strictly the law was actually enforced. Were most applications granted or denied? It wasn’t clear from the record, and it could affect their view of the case. Shouldn’t the case be sent back for more findings?

The six conservative justices, however, seemed supportive of Clement and skeptical of the New York law. Their questions centered on how broad a remedy he was seeking and what such a ruling might mean for “sensitive places” e.g. courthouses, stadiums, schools, and airports. Could people carry their concealed weapons into such areas? These questions appeared to presuppose that the law was problematic.

Justice Kavanaugh seemed to open the door to a revision of the law to make it a “shall issue” one similar to laws in other states, i.e. the state “shall issue” a concealed carry license provided certain criteria such as background check and firearms training are satisfied. Clement seemed to accept such laws as constitutional, giving the Court an opportunity to issue a narrow ruling striking down the law as written.

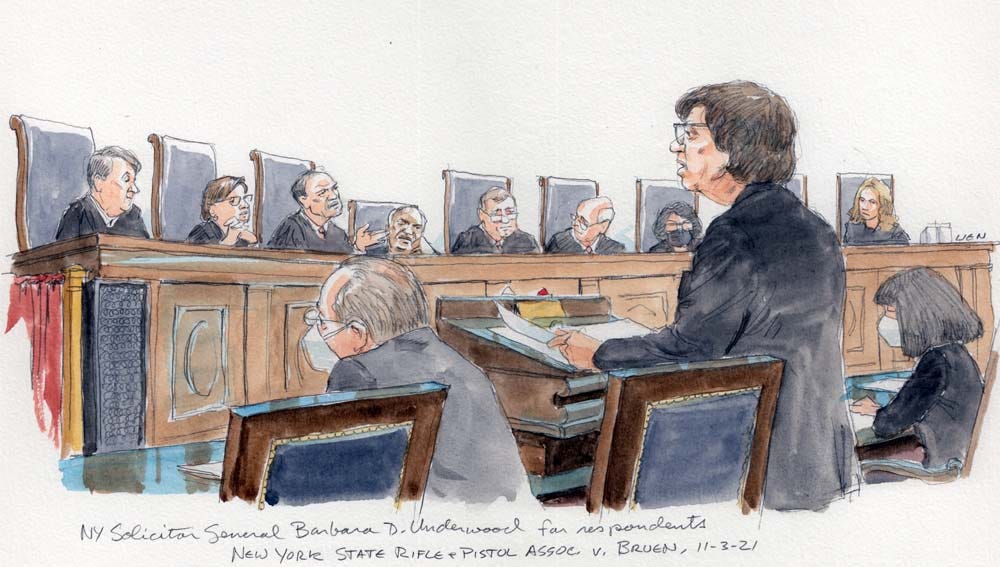

Arguing in favor of the law were the solicitor general of the state, Barbara Underwood, and the deputy solicitor general of the U.S., Brian Fletcher. Both Underwood and Fletcher emphasized that for centuries both English and American law have restricted the carrying of firearms in public in the interest of public safety, and New York’s law fit well within that tradition.

But the conservative justices were skeptical of the actions of the state, which rationalized greater restrictions on concealed carry in highly populated places while having fewer restrictions in less densely populated ones. Chief Justice Roberts observed that, logically, a person would have greater need for a concealed weapon in a more densely populated area. When Fletcher answered that the state needed also to consider the need for public safety, Roberts stuck to the question of self-defense. “How many muggings take place in a forest?” he asked rhetorically.

Justice Alito appeared the most hostile to the law among the justices, arguing that nurses, dishwashers and doormen without criminal records but who live in high crime areas would not be able to gain a license because they were not specifically targeted yet. How, he asked, “is that consistent with the core right to self-defense, which is protected by the Second Amendment?”

The conservatives seemed intent on placing the onus on the state to justify its restriction on concealed carry rather than the individual having to show a need. This indicated to observers that they intend to expand the right to possess a weapon in your home for self-defense, as announced in Heller, to the idea that anyone should be able to own a weapon and take it anywhere, even hidden, without having to explain themselves to a government official.

Fletcher held his ground, telling the justices that such an argument “assumes the conclusion.” The very question in the case, he said, is whether the Second Amendment guarantees the right to carry a handgun for self-defense without a demonstrated need to do so.

A decision is expected in 2022. Given the strong conservative majority, the best liberals likely can hope for is that the law is merely struck down as unconstitutional and the Court does not announce a major expansion of the right to concealed carry. But if Roberts and Alito are aligned on this already, we should anticipate and prepare for a broader reading of the Second Amendment, possibly including a ruling that the right to bear arms means to bear them anywhere but the most sensitive of areas, and that even as to those the government must show a compelling interest to restrict concealed carries.

Such an expansive read of the Second Amendment has long been a goal of conservatives, who along with the NRA have packed the Court with their allies. By next June, that investment may pay off.

I hit the ❤ button to indicate I read the article, but I really do not ❤ any of this. 😪