I first heard about the crisis at Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) through an email. Full disclosure: My family company is invested in a few start-ups that kept the bulk of their funds at SVB. So I was receiving the email because the fate of some of those companies was now up in the air.

On social media, and in private chats, there was a lot of concern, some bordering on panic. While the government stepped in to seize control of the company on Friday, already some automatic payroll deposits at other banks were failing. A lot of companies that were locked out of their funds feared that, come Monday, they wouldn’t be able to pay salaries. Every small venture wanted to know how much of its funds was at risk of being totally inaccessible, or worse, evaporating entirely. It was a very long weekend for many.

I wanted to better understand what was going on, so I spent time this weekend learning about SVB, the banking system, and why the federal government needed to act. I soon realized that a lot of my assumptions about the situation were wrong, and I also saw this was often the case in online takes elsewhere. So with the caveat that I’m neither an economist or a financial expert, which in some ways makes me well-suited to pen this layperson’s explainer, let’s take a look at some of those incorrect assumptions, and let’s get to some common questions that I hope I can now help answer.

SVB failed for a really basic reason

In the classic 1946 movie It’s a Wonderful Life, Jimmy Stewart plays George Bailey, who faces a crisis when customers at his family’s business, Bailey Bros. Building & Loan Association, panic and clamor to withdraw their deposits. George is able to calm them by explaining how the system works—and importantly how it all falls apart if everyone wants their money all at once.

That’s because every bank, whether big or small, operates on the same principle: It receives short term deposits from customers, who have ready access to their funds, and it uses those to make longer term investments. The bet made by the banks is that they can make more on the long-term investments than they have to pay out in interest to the short-term depositors. But there’s a catch: The banks have to have enough short-term cash on hand to cover the case where many customers want to withdraw money. And sometimes, as George Bailey explained, the actual cash isn’t immediately available because the bank used it for other things—just like it’s supposed to.

So what happens when too many people want to withdraw at once? The bank has to sell those long-term assets to raise enough money to cover the demand for cash, and that can make it start to take big losses. When word gets out that a bank may be in trouble, it sometimes causes a run on the bank : Fear spreads among depositors that, if they’re last in line to get their money out, the bank will have failed already and they’ll be stuck without recourse.

And that’s precisely what happened with SVB and its customers. So it’s a really old story, but with a new twist.

There are some protections in place against this because this kind of bank run happened a lot during the Depression. Back then, the government set up the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as an independent agency to insure depositors, currently up to $250,000 per customer, in the event the bank is unable to pay them back. Banks regularly pay into a big insurance fund, so the FDIC is self-financed by the industry and not by taxpayers.

But in SVB’s case, there were many tens of thousands of business customers who understandably had far more than $250,000 in deposits. These included thousands of start-up companies who use funds from investors like private equity and venture capital companies to pay employees and vendors and to make future capital investments. Moreover, like the small town in It’s a Wonderful Life, in the start-up and venture community, news travels very fast, and so therefore does panic.

So, wait, how did SVB actually mess up?

We’re used to hearing about big banks failing (remember Lehman Brothers?) because they made wild speculative bets or created money out of thin air using new, unregulated products with names like “mortgage-backed derivatives.” But in SVB’s case, the bank did something no one usually associates with a big bank failure: It bought boring, long-term government bonds.

According to expert Marc Rubenstein, who analyzes financial institutions for a living, there were three things that generally led to a collapse of SVB.

First, during the boom days of venture capital, when money was very cheap if not free because of low to zero interest rates, SVB was the recipient of huge influxes of capital. Hundreds of billions of dollars. Its bank deposits tripled to $198 billion, in fact.

Next, it had to figure out where to invest that money. Its own customers didn’t really need that much in loans, especially when interest rates were so low and they were already funded by investors. So SVB bought securities, especially government and mortgage bonds. Here, it’s important to note what kind of bonds it bought. The bulk of its purchases went to long-term bonds. Those pay out higher yields in general than ones you can sell in the short term, but as interest rates rise, their value on paper plummets. After all, who wants to hold a long-term bond that pays a lot less than what’s now available? But here’s the thing: The paper value of long-term bonds doesn’t actually need to be “marked” to the market value on the books. They’re usually just assets that get held to maturity, pay out their interest rate and pay back the principal, and then expire, rolling off the balance sheet.

Finally, here’s where it all came together in a big mess. When the tech boom faded, companies started asking for more of their money, but without many new deposits coming in, SVB was in a bind. It couldn’t sell its long-term assets without taking enormous paper losses. Instead, it sold $21 billion in short-term bonds, taking a $1.8 billion loss. Then it tried to raise money from investors to offset that loss, but that effort failed, leaving a hole on SVB's balance sheet. When the VCs saw that hole, some of them advised their portfolio companies to withdraw their funds. Word got out, and that’s what caused a run on the bank and its spectacular collapse.

So, is SVB getting a bail out now?

In a word, no. Unlike in 2008, when the government came in to rescue big banks, this time the Biden Administration is letting the bank fail. That means that its shareholders and debt holders are going to take a big hit, and all of its top executives will lose their jobs. It is a far cry from what happened 15 years ago.

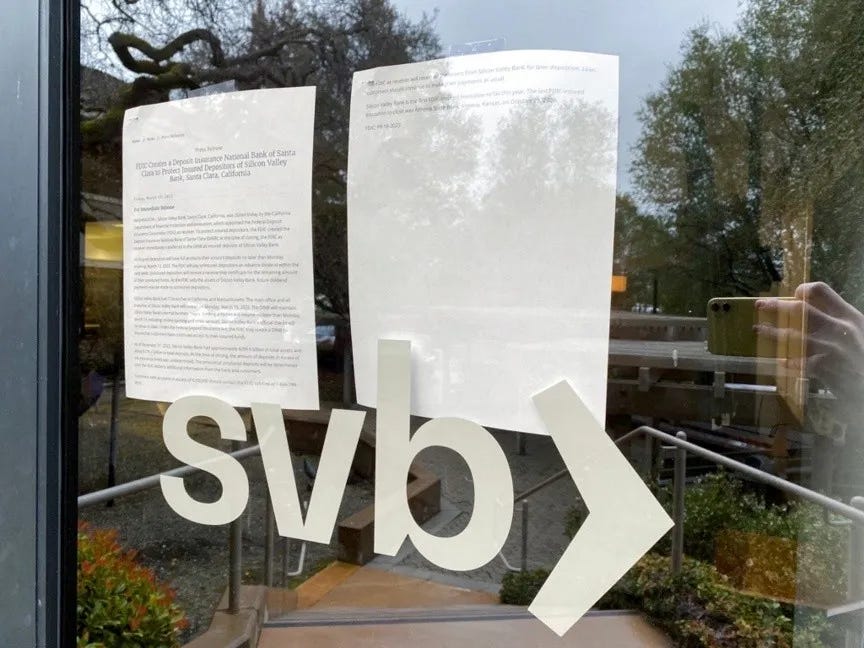

Instead, the government has seized control of SVB (along with another bank that was teetering, Signature Bank of New York) and assured depositors, and importantly those with deposits over $250,000, that they would have full access to their funds come Monday morning.

At SVB alone, there are 34,766 of these companies, all with employees and invoices to pay. If those depositors can’t access funds, it will cause a ripple effect that could compound the panic in the financial sector. Families and small business vendors depend on paychecks and payments, and the last thing our recovery needs is a huge shock to the system and more financial uncertainty.

But won’t this cost taxpayers hundreds of billions?

This is the part that is somewhat harder to understand. How is it Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen can assure the public that taxpayers won’t be left holding the bill?

The government is assuring companies that they can have access to funds in order to stop a further run on the bank. This way, they don’t feel the need to withdraw all their money right away because the government has given its assurance that the money is safe and available. Remember that most of SVB’s money was in long-term bonds that will eventually mature and pay back with interest. So there’s plenty of money available in the long term to make depositors whole. What SVB faced was an inability to cover the short-term crisis.

The mechanism the government is proposing is actually also intended to prevent other runs at other banks. It’s a loan pool set up by the Treasury as part of a program to allow banks to pledge their U.S. Treasuries and other safe government securities as collateral in return for loans of up to one year from the central bank. This will cover any possible panicked withdrawals by depositors because the banks will be allowed to obtain loans from the Treasury against those long-term bonds they can’t otherwise sell without taking a huge hit. (It’s a bit like being able to borrow against your 401K.) SVB is probably wishing that program were in place when it needed to cover the spike in demand for withdrawals, rather than having to sell some of its short-term assets at a loss.

But this is capitalism. Why can’t we just let rich VCs and their portfolio companies eat their losses?

We could, of course. But the trade-off is that we might create the very kind of uncertainty that is harmful to stable growth and financial sector health. Depositors need assurances so they don’t pull their funds out of other banks in a panic.

Also, and this is less understood, such a move would be bad for innovation and, as one example, especially bad for our planet. SVB was where most of the climate tech start-ups we will depend on to drive new technologies to solve our climate crisis kept their funds. As the New York Times reported, there were over 1,500 leading start-ups banking with SVB that are currently working to help stop global warming. Letting well-funded innovators twist in the wind might feel satisfying to some, but it’s really not a smart move for our society or planet as a whole.

It’s perfectly reasonable, on the other hand, to say to SVB shareholders and management that they need to own the errors of their ways. But the Biden Administration has decided society shouldn’t permit the mistakes of those big-wig bankers to harm innocent smaller businesses and working families, if we can devise ways to keep liquidity and confidence high.

Did deregulation contribute to the collapse?

This is something that will be fought over by the parties over the coming weeks. There are indications that the kinds of regulations, including so-called “stress testing” for smaller regional banks, that would have surfaced problems and kept this from happening were eliminated by the Trump administration in 2018. But there were also Democrats, including Sen. Joe Manchin, who pushed for that deregulation, so the political narrative isn’t so cut-and-dried here.

Still, this will be an opportunity, similar to the Norfolk Southern train derailments, for the nation to come to consensus that banks aren’t always able to self-correct on their own. After all, the CEO of the SVB, Greg Becker, was himself a director of the Federal Reserve Bank in San Francisco, at least until he was removed this weekend. He ought to have known the impact that a rising interest rate environment might have on the paper value of long term bonds.

Will the people who profited from this collapse pay a price?

There was a lot of anger directed toward VCs who pulled their own money out and advised their portfolio companies to do the same. For example, Peter Thiel managed to get his own company’s funds out completely before the collapse.

Was this fair and legal? We will have to see, and there should be investigations, particularly around stock sales by the top corporate officers leading up to this event. Were they in the know about the poor health of the bank? Did they conceal this from other investors? The White House has already signaled that it wants to get to the bottom of who is responsible and to hold them accountable.

In sum, when a crisis hits like this, it’s important to contain the damage, assess what happened, and try to prevent it from happening again. So far, it appears the Treasury has done a good job on all three, but it’s too early to tell whether there will be further knock-on effects, or whether other banks have made the same error SVB did in failing to adjust to a much higher interest rate environment.

It might also even mean that the Federal Reserve needs to seriously reconsider the stresses it is putting on the system through its relentless rate increases, so that it doesn’t further contribute to any other bank collapses. A pause to all of this, so that bankers and customers everywhere stop panicking, might well be in order.

Great explanation, Jay. I work in banking and was around during the 2008 crisis - this is definitely different. Clear and concise summary of the situation. SVB’s two main mistakes, imho, is that they weren’t diversified enough, so they were particularly susceptible to the fortunate of one industry (ie tech). The other mistake is not having a Chief Risk Officer for almost 8 months, so no one was there to tell them - “hey, maybe we should start scaling back some of these long term investments..”

Why do they keep raising the interest rates when it isn’t actually working to control inflation? It seems like it just puts additional strain on the average American who is already struggling with obscene price increases while still allowing corporations to bank record profits as result of their price gouging and failure to pay a living wage.