On Monday, a three-judge federal panel in Alabama, including two Trump appointees, issued a 196-page opinion striking down Alabama’s proposed redistricting maps and assigning a special master to redraw them.

Full disclosure: I didn’t have time to read it through. It’s 196 pages. But I did skim it, and I did read analysis by smart people who read it, to which I have some thoughts to add.

We could see this as just another redistricting case, where the state has lost because it so clearly deprived minority voters of fair representation through racial gerrymandering. There are plenty of those cases floating around, especially across the South. Florida’s maps were just struck down as unconstitutional by a federal judge for the same reasons, and Louisiana’s maps could be next.

But to me, this decision in Alabama was something more because of why the panel’s second ruling was necessary. Behind the usual bad faith voter disenfranchisement case lies a higher stakes case of FAFO. The bad actor here was the state of Alabama itself, and it is apparently trying to F with the federal courts, including the Supreme Court. And that makes this case both fascinating and noteworthy.

Let’s take a closer look.

The SCOTUS surprise

To understand how we got to this point, we need to rewind to June of this year, when a 5-4 decision—written by Chief Justice John Roberts and joined by Justice Kavanaugh and the three liberal justices Kagan, Sotomayor and Jackson—shocked voting rights activists and GOP powerbrokers alike.

In Allen v. Milligan, the Court struck down Alabama’s racially gerrymandered congressional district map under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

To give a bit of context for why this opinion came as a shock, when I was in law school way back in (eh hmm) 1994, I wrote a paper in my Voting Rights class on how SCOTUS had already fired a warning shot across the bow of Section 2. That part of the law expressly permits the use of race to create “opportunity districts” for minority voters where they can have a fair chance at electing representatives from their own communities to Congress. Think of it as a kind of affirmative action for minority representation. Because the Court had already begun to signal its displeasure at any law that was not completely colorblind, the fate of Section 2 lay in doubt.

That was nearly 30 years ago.

My fears, along with those of voting rights advocates, were further confirmed when Chief Justice Roberts eviscerated another part of the Voting Rights Act—Section 5—in the Shelby County v. Holder decision in 2013. That opinion gutted the practice of “pre-clearance” for jurisdictions that had a history of suppressing minority votes. Before Shelby County, when a state like Alabama went to redraw its maps, or pass any kind of law that could have the effect of suppressing minority votes, the Justice Department or a judge would have to pre-approve the change, meaning clear it before it got implemented. But Justice Roberts thought, “Hey, we don’t need that any more, no one acts so racist these days!” So he ruled Section 5 unconstitutional as applied and told Congress to fix it. (Congressional action has been blocked by the filibuster ever since.)

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, may she rest in peace, famously warned in her Shelby County dissent that “throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

And as Alabama showed with its first map, which drew a majority Black congressional district out of existence, we are definitely back in that racist rainstorm. In fact, we never left it.

Two things to take away from Allen v. Milligan that allowed voting rights advocates to breathe a little easier:

First, Chief Justice Roberts acknowledged concerns that Section 2 “may impermissibly elevate race in the allocation of political power within the states,” and he observed that the opinion “does not diminish or disregard these concerns.” However, he went on to say that it “simply holds that a faithful application of our precedents and a fair reading of the record before us do not bear them out here.”

Second, Justice Kavanaugh wrote a concurring opinion where he implied that there was a time limit to affirmative race-based considerations when it comes to political representation, noting that “the authority to conduct race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future.”

(Justice Thomas wrote a hopping mad dissent, but it’s not really relevant or helpful to our discussion here.)

Alabama thumbs its nose

The case was already enough of a shocker with that surprise SCOTUS opinion. Everyone had assumed Chief Justice Roberts would use the case to kill what remained of the Voting Rights Act, a law he clearly had disdained for so long. But perhaps something about the “fair reading of the record” stayed his hand.

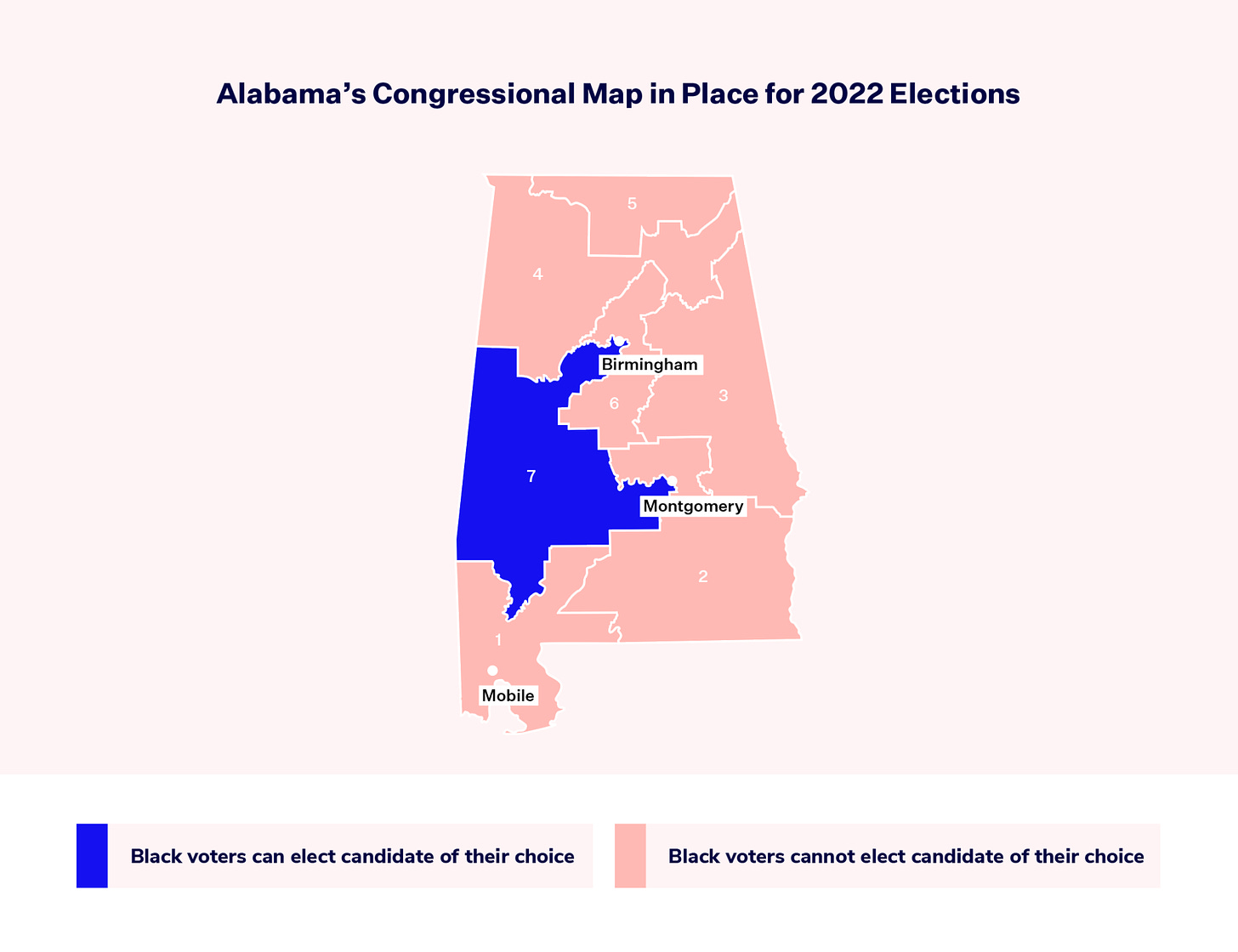

Alabama had redrawn a map to give white representatives 86 percent of the congressional districts, leaving only one Black congressional district out of seven—in a state that is nearly one-third African American. One-out-of-seven representatives is a lot fewer than one-out-of-three. But the way they drew the map was blatantly discriminatory and was itself racially motivated. Here is the now-ruled illegal map that was still in place for the 2022 midterms, courtesy of Democracy Docket.

This is an example of both “packing” and “cracking” in gerrymandering. Black voters are “packed” into the blue area, District 7 above, which extends out finger-like to grasp both Birmingham and Montgomery and pull these mostly Black voters together into the same district. Black voters in districts bordering the blue distract then get “cracked” apart and lumped in with white rural voters, diluting their votes and rendering them permanently ineffective.

As Mark Joseph Stern of Slate notes, Alabama remains stuck in the Jim Crow era. Its very constitution contained explicitly racist language to “establish white supremacy in the state”—a provision that wasn’t removed until 2022. The state hasn’t elected a Black official to statewide elected office since Reconstruction.

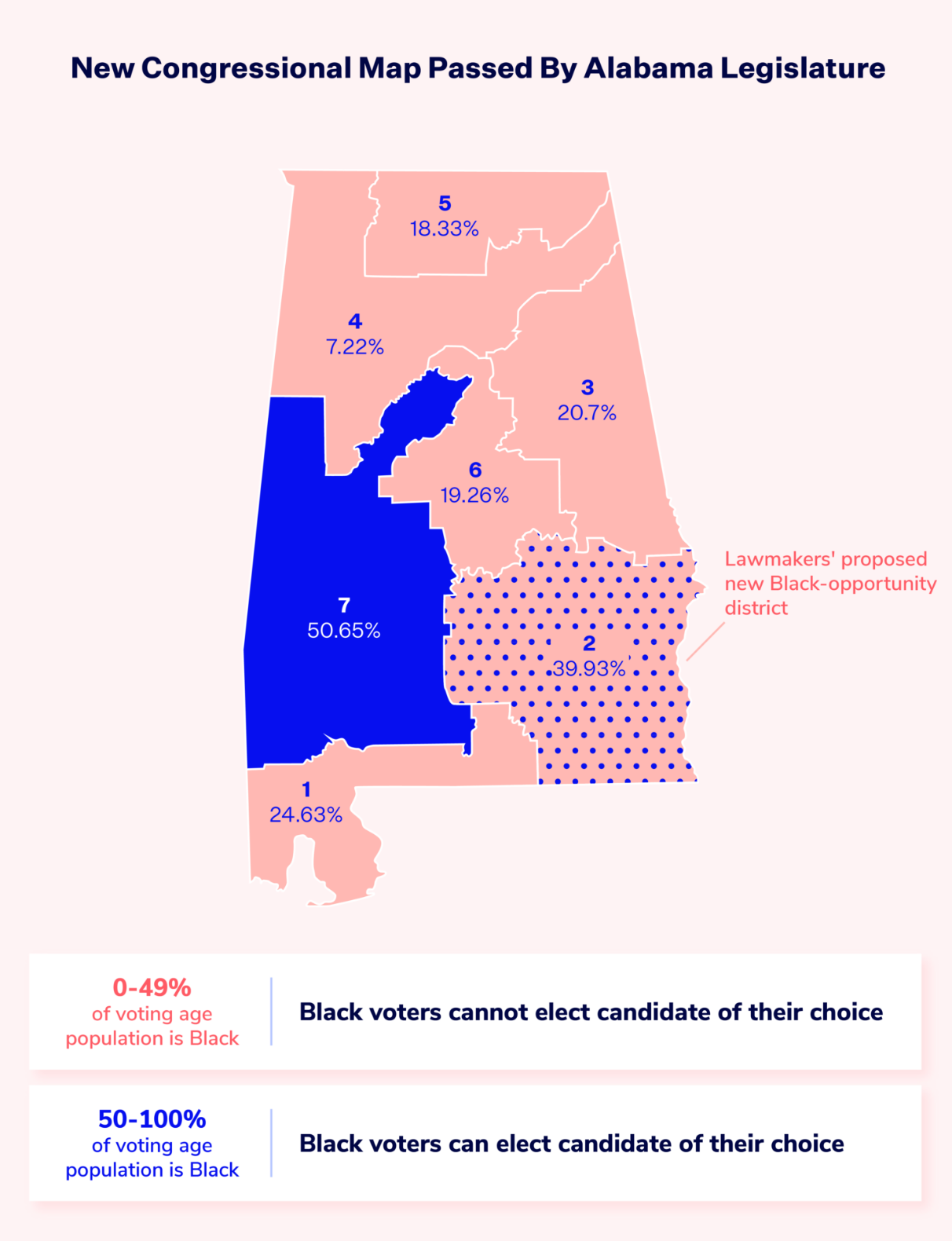

So when the predominantly white legislature pushed through the above map, voting rights advocates sued, led in part by former Attorney General Eric Holder, claiming the map’s elimination of the second “opportunity district” for Black voters was a violation of Section 2. The three-judge panel agreed, and it ordered a new map with a second opportunity district where Black voters had a majority or “something quite close to it.” (Holder was named in and had lost the Shelby County case, so this decision plus the affirmation by SCOTUS must have been a sweet victory, indeed.)

But then, what did Alabama do in response? It came back with a completely noncompliant map. The new proposed map ignored SCOTUS’s affirmation of the panel’s decision. It contained a second district that had a Black voting age population that was less than 40 percent. Something “quite close to” a majority? Hardly.

I want to be clear about what happened here. A state legislature, backed by its governor, ignored the direct order of a federal court that was backed up by the U.S. Supreme Court. Why would they do this? As Stern pointed out,

House Speaker Nathaniel Ledbetter gave the game away when he explained that “the Supreme Court ruling was 5–4, so there’s just one judge that needed to see something different.” His goal was not to draw a lawful map, but to peel off a conservative justice from the Supreme Court majority. Indeed, he and his colleagues did not even claim to follow the court’s order. They simply insisted that their new map restarted the entire legal process, erasing the court’s past analysis and forcing it to begin again from square one.

That “one judge” is undoubtedly Justice Kavanaugh. Ledbetter and his cronies want another shot at SCOTUS with the hope that Kavanaugh will look at this new map and say, “Eh, good enough.”

That’s not how the law is supposed to work, and I’d be very surprised if Justice Kavanaugh didn’t see through this instantly. Permitting such a brazen disregard for an order to stand would result in the High Court’s authority being undermined. It would suggest that the best strategy to get what you want is to refuse to comply with the Court’s ruling, hoping for another shot.

The District Panel’s new opinion was seething

Alabama’s gamesmanship also made a lot of extra work for the three-judge panelists. As I noted with some distress, the panel’s second opinion was 196 pages. On the bright side, it fairly oozed with ire. There’s this gem:

We are not aware of any other case in which a state legislature — faced with a federal court order declaring that its electoral plan unlawfully dilutes minority votes and requiring a plan that provides an additional opportunity district — responded with a plan that the state concedes does not provide that district.

Here’s more, where the court in a single paragraph uses “deeply troubled,” “disturbed by,” and “struck by” in back-to-back sentences.

We are deeply troubled that the state enacted a map that the state readily admits does not provide the remedy we said federal law requires. We are disturbed by the evidence that the state delayed remedial proceedings but ultimately did not even nurture the ambition to provide the required remedy. And we are struck by the extraordinary circumstance we face.

That is judge-speak, by the way, for “Seriously, WTF are you trying to pull?”

Alabama also had a truly cynical argument with which it hoped to rope in Justice Kavanaugh. It claimed that whenever a state legislature draws a new map, courts have to assess it anew, while allowing elections to proceed under it. If the map is struck down, that ruling has to be on hold in light of upcoming elections. And then it has to wait for the legislature to draw new maps. Rinse and repeat, until the clock runs out.

If you think this could never happen, it actually just did in Ohio. There, in advance of the midterm elections, the state Supreme Court kept striking down maps and sending them back to be redrawn, but then time ran out and a federal court finally stepped in to say that the maps had to stand for the midterms. The experience emboldened legislatures like Alabama’s to try it in federal court, too.

The panel addressed this troubling question head-on. “The state’s view…allows the state to constrain (indeed, to manipulate) the court’s authority to grant equitable relief,” wrote the panel. Alabama seeks to create “an endless paradox that only it can break, thereby depriving plaintiffs of the ability to effectively challenge and the courts of the ability to remedy.”

The panel has now appointed a special master to draw the district lines.

Alabama has vowed to appeal the ruling. But their case may get an icy reception before SCOTUS. After all, Alabama’s defiance of the federal panel was tantamount to a defiance of the High Court itself, which had affirmed the ruling below. Through its actions, the state has made this case about whether the Supremacy Clause has any meaning and whether SCOTUS is actually toothless in the face of such defiance.

Good luck with that, ‘Bama.

Thank you for choosing this topic to analyze for the non-legal among us.

A phrase that you have used many times, "run out the clock," is beginning to resonate some alarm for me. Run out the clock for.....what? Simply the next election, then the one after that, and so on? At some point the changing demographics of this country are going to render that strategy ineffective. UNLESS....there is a tacit underlying conviction that they only have to delay just long enough to get a white supremacist autocracy established in Washington, at which point their actions will no longer be challenged by anyone and elections themselves become superfluous.

‘That is judge-speak, by the way, for “Seriously, WTF are you trying to pull?”’

This is why I love your pieces😂😂😂