Congressional Recession

And a stick of constitutional dynamite at the end of the rabbit hole

Democrats won’t soon forget that the GOP spent years blocking Biden’s judicial, Pentagon, Justice and State Department nominees. They used all manner of parliamentary holds, privileges, and drawn out committee hearings to slow walk many of his appointments.

Because turnabout is fair play, the incoming Trump administration faces the possibility of this happening to its nominees as well—similar to what he experienced in his first term. Trump is expected this time around to put forth some truly horrible choices, particularly in the Justice and State Departments and the intelligence services. That could garner pushback, even from more centrist GOP senators.

Sensing that possibility, Trump is looking for a way around the Senate confirmation process altogether. In a post on Twitter, Trump moved preemptively to require whoever becomes Senate Majority Leader—a race being determined by secret ballot this week—to back “recess appointments” for his picks.

“Any Republican Senator seeking the coveted LEADERSHIP position in the United States Senate must agree to Recess Appointments (in the Senate!), without which we will not be able to get people confirmed in a timely manner,” Trump tweeted on Sunday. “Sometimes the votes can take two years, or more. This is what they did four years ago, and we cannot let it happen again.”

At the same time, he wants GOP Senators to block judicial confirmations by the Democrats, who still control the Senate until January. The irony of this position was not lost on observers. “President-elect Trump wants any GOP Senator in the leadership to commit to support his recess appointments—but to deny them to Democrats before his inauguration,” wrote legal analyst Lisa Rubin.

The power to use recess appointments is one that has been denied presidents for around a dozen years by Congress refusing to ever officially adjourn. A change in this practice to benefit Trump today would be a significant loss of stature and power for the body as a whole.

But as I followed this trail down to the very letter of the Constitution, I came upon a dangerous exception I’ve never before considered, one that could swallow the rule. It’s a few words that could turn Congress into a mere afterthought on appointments, and if extended further, could render it moot.

Because the stakes are so high, and the rabbit hole begins with basic questions over recess appointments, we need a refresher on what such appointments really are. Specifically, we need to understand whether Trump can really get around Senate confirmation by making appointments when Congress is out of session. Fair warning that this gets us into some pretty thick parliamentary weeds, but I will try my best to hack my way through them here.

Even if Democrats successfully block Congress from going into recess using parliamentary maneuvers, this could set up a showdown where Trump tries to force Congress into adjournment by decree—something he threatened but failed to do near the end of his first term.

More ominously, we need to understand what could happen if Trump does force Congress to adjourn and then, per the Constitution, gets to choose when it is able to recommence its business. And that frankly is more than a bit unnerving. It should give any senators pause before they scheme to hand the recess appointment power over to Trump by way of presidential decree.

Advice and consent

To understand the issue of recess appointments, we first need to remember a key function of the Senate. Under the “advice and consent” clause, the Senate must approve all of the president’s nominees as well as all senior positions within the government. That’s over 1,000 appointments. This power was put in place by the Framers to prevent cronyism and extremism, with the idea that the Senate would tend to protect its own power against an overzealous Executive Branch.

When the Senate is controlled by the opposite party, the “advice and consent” clause places a substantial limitation on the kinds of nominees the president can push through. But even when the Senate is controlled by the same party that holds the White House, the Senate has historically been reluctant to cede too much authority by rubber stamping every pick.

We’ll have to see if that holds in the bend-the-knee era of MAGA Trumpism. A key test of that is whether an extremist loyalist like Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL) or an “institutionalist” like Sen. John Thune (R-SD), the current minority whip, succeeds Sen. Mitch McConnell as Senate Majority Leader. Through pressure on the contenders via social media, Trump is trying to force the candidates to pledge in advance to allow recess appointments of his nominees.

Thune has responded rather vaguely that “all options are on the table” and that he is “open to it,” while another top contender, Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX), merely repeated a truism in response: “The Constitution expressly confers the power on the President to make recess appointments.”

Recess appointments

When Congress is out of session, the U.S Constitution expressly authorizes recess appointments. It says in relevant part,

The President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.

In olden days, this made a lot of sense. The Senate was out of session about as much as it was in session. Senators went home from Washington by buggy and it took days. Recess appointments were a practical solution, not a political one.

Today, the Senate is largely in Washington and goes home on far shorter recesses and can be back in a matter of hours. The timeline specified in the recess appointments clause basically means that any such appointments made by Trump would last through the end of 2026. That’s a long time by modern political standards, so if Trump pushed a lot of these through, it would effectively gut the Senate’s traditional check on presidential power.

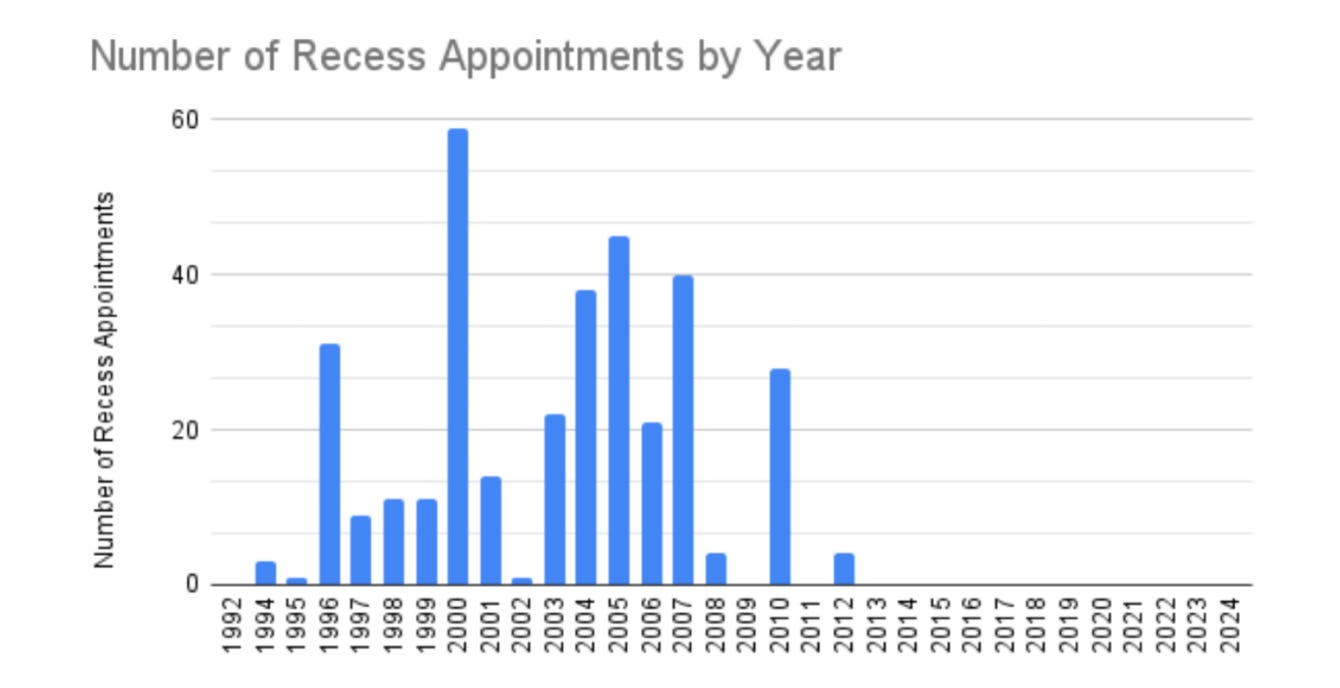

While this may seem like a huge and crazy loophole that was put in a long time ago, historically speaking, recess appointments have not been used to fill many federal vacancies. Presidents have understood that to do so means to thwart the Senate, and it doesn’t win you influence or friends to treat them all like potted plants. So the use of recess appointments has been fairly sparing, the highest in recent history by Bill Clinton in 2000. And over the past dozen years, they have not been used at all.

To understand why, we need to rewind to the early 2000s. That’s when the Senate began to use “pro forma” sessions to prevent George W. Bush from making so many recess appointments. These are real sessions of Congress, even though nothing is really happening and they’re just keeping the doors open.

In 2012, President Obama was facing a very hostile Congress, and they were obstructing his agenda by refusing to seat his appointees. So he tried to slip in an appointment during a brief, three-day recess. That got blocked by the Supreme Court in a 9-0 vote. It ruled that the recess was not long enough, and that you need at least 10 days. But it also held that pro forma sessions do mean there is no actual recess, and therefore the president cannot exercise the recess appointment clause during them.

The reason we have seen no recess appointments since 2012 is simple: Since then, Congress has never officially gone into recess. It has stayed open more or less to prevent recess appointments from happening. This was true even during Trump’s first term, when the GOP controlled both chambers of Congress.

Notably, even while pro forma sessions were established again at the start of Trump’s first term to try and block him from appointing really crazy people, in April of 2020, during the height of Covid shutdowns, Trump threatened to adjourn Congress to make some recess appointments. But the Constitution stood in his way. Let’s look at that next, because if Trump has tried to do something before, you can bet he’ll try again.

Wait. Can Trump simply decree Congress to be adjourned? And for how long?

Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution authorizes the President, “in Case of Disagreement between [the House and the Senate] with Respect to the Time of Adjournment,” to “adjourn them to such Time as he shall think proper.”

The prerequisite that the House and the Senate must disagree over the time of adjournment was what stopped Trump back in April of 2020. At that time, Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) were in agreement that the adjournment would be January 3, 2021, and further that they would not be changing that date.

One way to achieve recess appointments is to have likely House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) work with the next Senate Majority Leader to adjourn Congress for a period of at least 10 days. During that time, Trump could make recess appointments, at least under the rule established by the Supreme Court.

That raises three important questions: 1) Will the House and Senate collude to permit Trump to do this, 2) can Democrats block it somehow, and 3) what happens if Trump just decrees Congress to be adjourned?

The answer to the first question about collusion isn’t clear. A lot will depend on who is elected Majority Leader in the new Senate. If the new Majority Leader wants to assert any kind of power for himself, ceding all “advice and consent” power in advance and allowing Trump to back-door all of his nominees would be ill-advised. Still, we are in a new MAGA-controlled government, so I wouldn’t put it past the new Majority Leader to go along with such an unprecedented move.

The second question about whether Democrats can block Congress from recessing is a bit murky. Normally, Democrats could filibuster any non-budgetary resolution. So even if the House passed a resolution to adjourn, forty Democrats could stop it. However, as Prof. Steve Vladeck discusses in his newsletter today, motions to adjourn are the rare kinds of motions not subject to debate, and therefore there is nothing to filibuster.

Perhaps. But there’s still the possibility of amendments to the motion to adjourn, which in theory would be subject to debate and therefore the filibuster. (I warned you, we’re in the weeds!) Republicans could try to get around this by creating new, clean adjournment resolutions, but each attempt could be subject to a new amendment, and around we go again.

The answer to the third question is more ominous. Any GOP Majority Leader devising a way to give Trump not only the power to adjourn Congress but also to keep it adjourned “to such Time as he shall think proper” risks creating a huge constitutional crisis.

Let me explain. What if Congress can’t agree on a recess because Democrats successfully block it, but then the circumstances still permit Trump to simply decree that Congress is adjourned? Trump then could further decree, “Sorry, you don’t come back into session until I say so,” citing the plain text of the Constitution. Instant constitutional crisis.

The Supreme Court was willing to give Trump near total immunity for his actions. But will it also countenance him rendering an entire other branch of government powerless because it can’t come back into session until Trump gives the go ahead?

Bottom line is, if the House and Senate collude to cede a core congressional power to the incoming Trump White House, they should understand what they risk. It could result in a Star Wars empire-level power grab that even lower information voters should understand isn’t right or normal.

If elected Senate Majority Leader, John Thune would do well to remember his own words from 2014: “When the president couldn’t get his appointments through the Senate, he decided to ignore the law and attempt an end run around Congress…. Congress, not the president, has the authority to determine its own rules.”

Correction: I had stated George W. Bush was the highest number of recess appointments in recent history in the year 2000. That should have been Bill Clinton. It’s been corrected.

It seems to me that the plan is simple, weeds notwithstanding: Adjourn permanently, and that’s it, just like Germany in the 1930s. Why is there even a doubt that this is where they’ll go? The question is, what preparations are being made to prevent it, or is prevention just a pipe dream, and this is what’s going to happen, get ready?