My little Riley loves her crinkle book. Maybe it’s the sound it makes when you turn the pages, maybe it’s all the extra textures and shapes she can play with. I’ll often find her with both hands on that book.

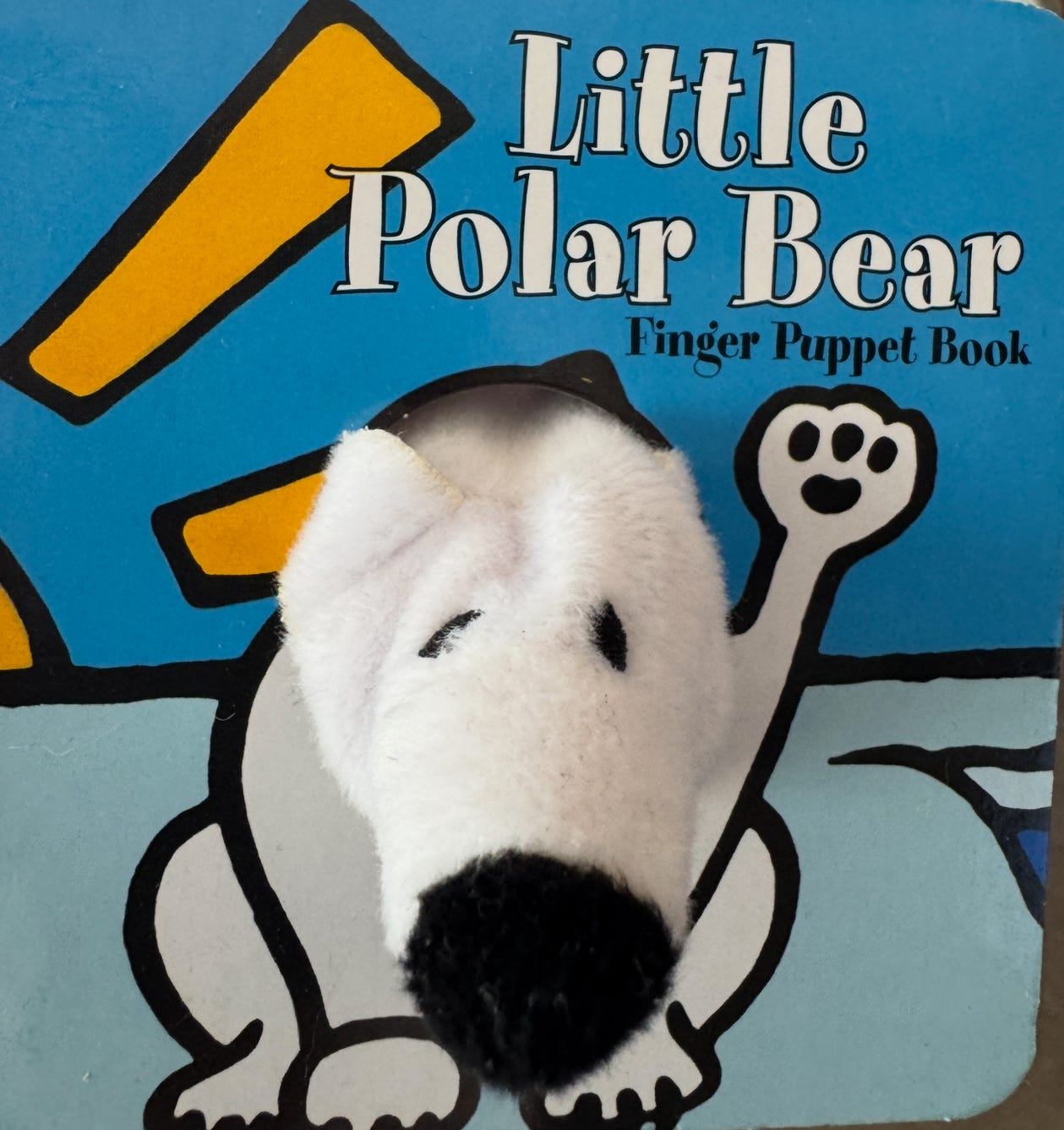

She has other favorites: Little Polar Bear, because her Ba can put his finger into the puppet and move it around, and it makes her giggly.

Or Never Touch a Porcupine, probably because it also has so many different surfaces she can interact with, even if she doesn’t understand the words yet.

Riley’s love of books matches my own. I spent my childhood absorbed in fantastical stories: The Chronicles of Narnia, the Brothers Grimm fairy tales, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings series. Stories of heroism, morality tales, long quests—they held my rapt attention throughout childhood.

It wasn’t until much later that I understood something key to my own adult identity: People like me weren’t actually in any of those books. Even though I imagined myself there, wandering through those mysterious lands, I was always a spectator, never a main character.

I often wonder how to approach this tension with my own kids. I want to share the stories I loved as a boy, but all of them feature white heroes, mostly men and boys. The stories are wonderful, but what kind of message would that send, even subtly, to a little Chinese girl like Riley? I could switch to others, but there are only so many Mulan stories made for English speaking audiences, and I would lose the chance to share a connection from my own childhood to hers.

Sure, I could build some kind of Great Wall around Riley, tell her about brave and smart women throughout history, read only Chinese stories to her, let her live a safe and protected life in her early years. But it won’t be long before she starts to ask questions. If women are so smart and such great leaders, why has there never been a woman president? If being Chinese is something we should proud of, why are kids making fun of me?

Far better to tell her the more complex truth, even as we find joy in the stories. These books were written mostly by men, mostly of European heritage. So we’re only getting a small slice of the world through them, even if that slice gets top billing nearly all the time. Riley will have to learn to deconstruct the world, even as she makes her way in it.

Raising children in a world turned upside down isn’t going to be a picnic either. We can read about the way things are supposed to be—with freedom, equality, and no tyrants ruling over us—but we aren’t living up to that. Not even close. Explaining that will be important.

I’m going to tell my kids that they were both born in a period of great transition, one with upheavals and uncertainty. I’ll explain that history is like the weather: While skies are normally blue and the wind gentle, sometimes great, dark storms descend. When they do, we are all left running for cover, huddled together for protection.

No one gets to decide what eras will overlap their lives. With any luck, and a lot hard work by the people, this storm will pass, too, and there will be blue skies again.

On why people who look like us aren’t much in the books, I’ll explain that we’re part of a great quest ourselves. One day, there will be just as many fantastic stories to read and movies to watch, where the main characters are us and the stories are about our lives. Our own family is a part of that quest, and your Ba has worked hard his whole life to help make that dream come true.

I’ll say to Riley, “One day, maybe, you’ll look around and see that things look and feel just about right, just about fair. And you’ll read stories to your own kids, ones that you loved when I read them to you. You can tell them about a time, long time ago, when the stories were all one way, and mostly about boys. But then a brilliant rainbow appeared after the storm, and the world had plenty more colors and brightness to fill our lives.”

“And you can tell them, no one thinks much any more about whether the president is a man or a woman or somewhere in between, or what the color of their skin is, or where their parents came from, or who they love. It took a long while, and there were some very hard times along the way. But we always believed this story would lead us toward a happy ending, and we’re back on the right path.”

Not gonna lie, I teared up a little when I read this. You're an incredibly thoughtful person so I'm not surprised that's how you are as a parent. Riley is a very fortunate child.

I love this. Your storm analogy is perfect. Your little one is just beautiful!