In lieu of my regular look ahead to the week’s news, and because it’s Mother’s Day, I wanted to hit pause on politics and instead share with you an excerpt from my upcoming book, MA IN ALL CAPS.

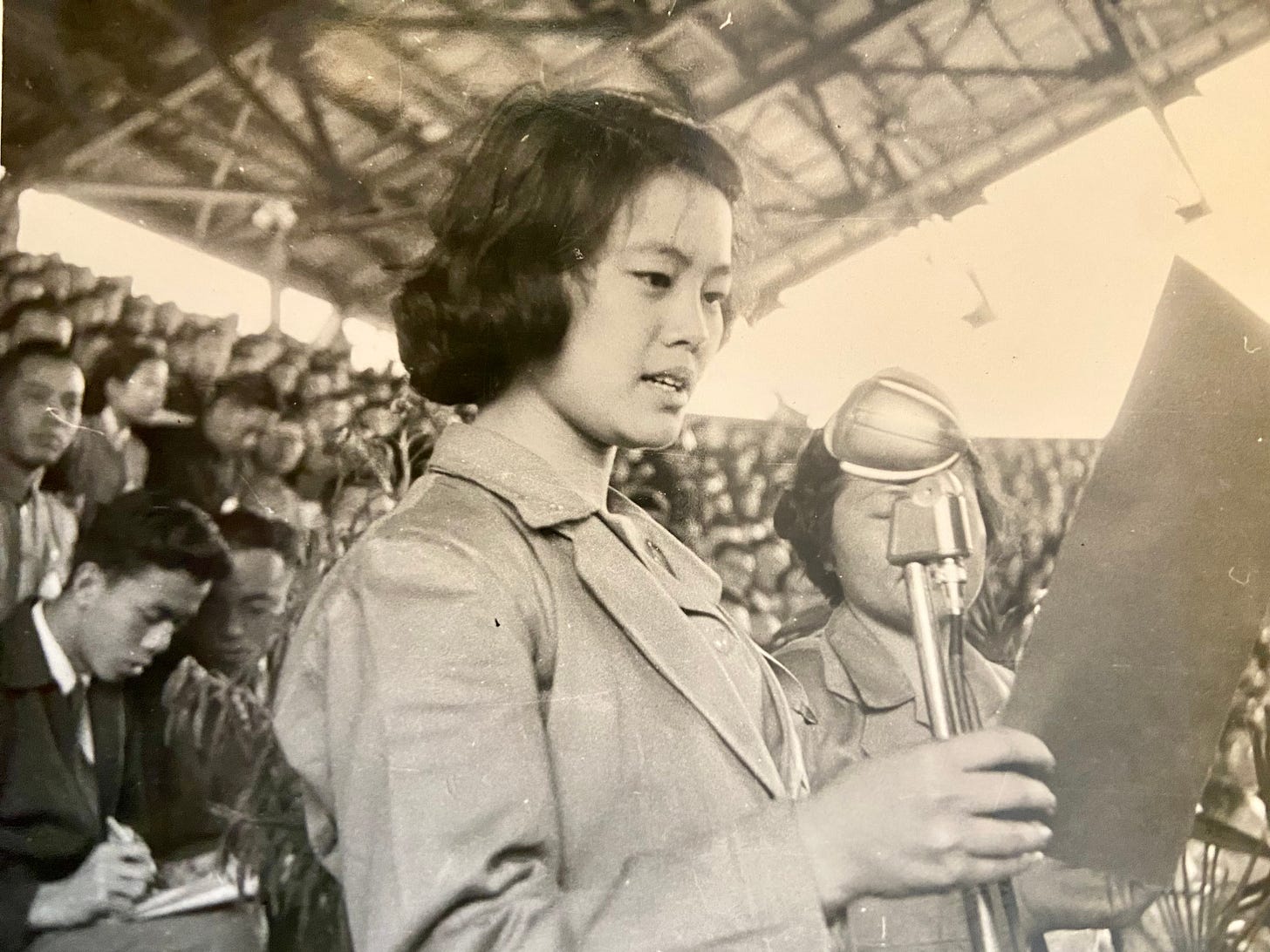

Many followers of my Facebook page know Ma as the blunt, quirky and hilarious woman she was. Fewer know about the incredible life she lived through historic times last century. I wrote the book to honor both aspects of her.

This is one of my favorite stories she told me of when she was a little girl growing up in China after World War II, before her family evacuated to Taiwan during the Chinese civil war.

Happy Mother’s Day. Ma, you’ve been gone six months, and that’s hard to wrap my head around. I still think of you each and every day.

August 1948, Nanjing, China

Ma was in third grade when her family resettled in Nanjing, with her father eager to serve in the new Chinese Republic. By this time, Waigong was already a well-connected politician, and because of those connections, as well as a bit of insider knowledge, they had a fine house in a fine neighborhood, by any standard.

On the walk to and from school, Ma regularly passed the Afghan Ambassador’s residence, the only truly distinct house in their area. Nanjing, like the rest of China, was still rebuilding from the war, but the capital and the wobbly government were hamstrung by civil strife. There were few established, diplomatic relations with any other nations, which were all waiting to see whether the Nationalists or the Communists would emerge in charge of the country.

“AS A RESULT, I NEVER SEE ANYONE BUT CHINESE FACE AROUND NANJING. EXCEPT THE AFGHANISTAN HOUSE.”

The Ambassador’s house was the most foreign-feeling place Ma knew, and she felt pulled to it each day, walking by it as slowly as she dared without drawing attention.

The house was palatial and magical. Exotic spices—cumin, coriander, and saffron—drifted in the air alongside mouth-watering, barbecued lamb. Ma sometimes heard strange, haunting music, voices that riffed along a mystical scale from somewhere within the home’s many chambers. The residence boasted multiple stories, with large, open, arched windows and ornate columns, and even a spacious balcony where she would sometimes get to see them: the two shimmering figures who were the wife and daughter of his Excellency, the Ambassador. They had matching long, dark, and lustrous hair, pinned with clips laden with what must be precious gemstones. Ma wished she could get a better look at their hair, even touch it with her hands. It seemed so much more luxurious than the straight, jet-black hair of her girlfriends or the graying coifs of her aunties.

Even more startling was their attire—or lack of it. Mother and daughter, confined to the house with no way to go about the city on their own, instead lay out on their open balcony with their skin exposed to the sun. Nanjing was very hot in the summer, and Laolao explained with a crisp judgment that foreigners sometimes took off their clothes to sai taiyang—bathe in the sunlight—so that their skin grew brown. This was the opposite of what was expected from women in Nanjing’s upper circles, where pale skin was prized, while dark skin implied too much time in the fields. But the deep color suited the Afghans, Ma thought, their skin shining like burnished copper, highlighting gigantic eyes and distinct, long, pointed features, earlobes adorned with hoops of gold and lapis lazuli. Though they never left the house, they wore heavy make-up, most notably, indigo eyeshadow to match their gems and chili-pepper-red lipstick. Ma was never permitted any make-up, let alone piercings, which her mother insisted was a sure sign of bondage and sexual license. As they floated above her on the terrace, Ma imagined them as living statues, two rock-hewn goddesses come to life, secreted away in a palace and bathing their bodies with sunlight.

The statues, it turned out, could also talk. The mother and daughter pair spotted Ma staring up at them one day, and to her horror, they waved and beckoned her closer. She looked about nervously. They were shouting encouragement in their mellifluous tongue, smiling and gesturing enthusiastically.

The daughter disappeared for a moment, then returned with brightly wrapped candies in her hands. She began to throw them down to Ma. With each toss, the daughter would laugh and clap whenever Ma caught one. The candies were multi-colored and various, orange and lemon and hawberry, tangy and sticky in the heat. For days afterwards, Ma hoarded them protectively, doling them out only as rewards and favors to her many cousins—well, at least the ones who pleased her.

The candy drop became a regular interaction and very much their secret. Ma would come by at least twice a week, if the sun was out, to see if she could catch another glimpse and gain another handful of treasure. Few could really see what mother and daughter were doing on that balcony (and would have frowned upon it had they known), and no one ever suspected where she got her fine candies either. She wondered what it must be like to belong to such a strange culture, where a mother would pass the time with her daughter as if they were good friends, instead of family. What an odd but thrilling arrangement!

“I COULD NOT IMAGINING LAOLAO, AND I TAKE SUN BATH TOGETHER,” Ma said with a laugh. “THAT WILL BE THE DAY.”

Their bikinis hinted at a world far more modern and even daring, ever just beyond reach, and hidden behind draped archways. Ma had seen a poster for the movie, “Arabian Nights,” and she often wondered if the mother and daughter had starred in the film.

“You never went inside?” I asked Ma.

“I NEVER WENT IN. JUST IMAGINING.”

But years later, with her memory fading, Ma told it differently, insisting that she had, in fact, gone inside the magical house. My brother and I pressed her for some details, but she couldn’t summon any. I wonder how powerful the longing had been that her brain now filled in the gaps.

In 1949, Waigong announced they were leaving, just ahead of the advancing Communist forces, and evacuating to Taiwan. Laolao let her anger uncoil, accusing Waigong of being little more than a war refugee, so often were they on the run. But to Ma, Taiwan sounded exotic and tropical, and the evacuation was like any other they had endured—but it came with her first plane ride this time. The family left first in a hurry, and the servants followed, packing up their belongings onto ships headed south and east. It happened so quickly Ma missed any chance to meet her strange Afghan benefactors in person, to inspect their bikini suits up close, or to touch their beautiful hair.

After her family fled, she wondered whether the two women knew where she had gone so suddenly, and she wanted badly to thank them for the candies and their kindness, and especially to warn them about the Communists who would never permit sunbathing—it was a bourgeois practice after all. They surely would expel the Ambassador back to Kabul for having made friends with the KMT. In fact, all the foreigners in Nanjing would probably be sent packing, and this made Ma sad. Even at her age, she understood that the Chinese did better when they had someone other than just Chinese around.

Many decades later, a resurgent consumer class of women in China would sport bikinis while sunbathing, though in moderation and often with thick sunblock on. They would also develop a thirst for rare gems and stones, especially the cold, blue treasures of Afghanistan. China’s burgeoning gem industry, through Ma’s friend, Meiling, at the Gemology Department, placed a special request with Ma, who was now far older than Laolao had been during the war, to see if she might safely obtain some from that embattled country.

Times had changed in Afghanistan. A woman like Ma could no longer travel alone to the border, let alone engage in commerce once past it. New religious laws prevented her from going, though she wanted badly to see the homeland of her mysterious neighbors. She wondered if the mother and daughter had escaped that country or been forced by harsh laws to hide their bodies and faces. Ma reluctantly sent Ba to retrieve the bounty instead.

“How was it? What did you see?” Ma asked him eagerly upon his return.

“Very poor,” Ba said. “And dusty. Dangerous to travel. Not much to see, really.”

Ma was disappointed. In her imaginings, despite its fall into violent and hard times, Afghanistan was not a land of war, terror, and death. It was where beauty lay on a balcony, skin the color of polished copper, always ready to throw down the finest of candies.

* * *

MA IN ALL CAPS will be available for pre-order on Kindle in the near future, with hard copies available upon launch. Watch this space for more information on how to order!

Jay, I loved reading this so much! Your abilities to engage and compel and clarify and question are as impressive in this memoir style as they are in political punditry. I can’t wait to read the book.

Beautifully written. In my imaginings I see your mother below that balcony and the beautiful women above. How all their lives changed from those treasured moments! Thank you for sharing. I look forward to the release of your book!