The Initial Census Figures Are Out. What the New Numbers Mean for 2022 and 2024.

The long-anticipated initial census numbers came out yesterday afternoon, and they left some Democrats wringing their hands and others breathing a sigh of relief. By some initial estimates, there had been up to 10 House seats expected to shift, mostly from Northern blue states to warmer Southern and Southwestern red ones. But yesterday’s announcement held that number to just seven: Texas will gain two, while Florida, Montana, North Carolina, Oregon and Colorado will each gain one; New York, California, West Virginia, Ohio, Illinois, Michigan and Pennsylvania will each lose one seat. The initial estimate of ten, said the Census, turned out to be an overestimation of the rate of population shift. (For those who were expecting the worst from a Trump-tainted process, this news was relatively welcome.)

Assuming these numbers hold (some states like New York may sue over the results, having reportedly lost a seat because of just 89 people out of a population of over 20 million), what does this mean, both for the presidential election in 2024 and more immediately for control of the House in 2022?

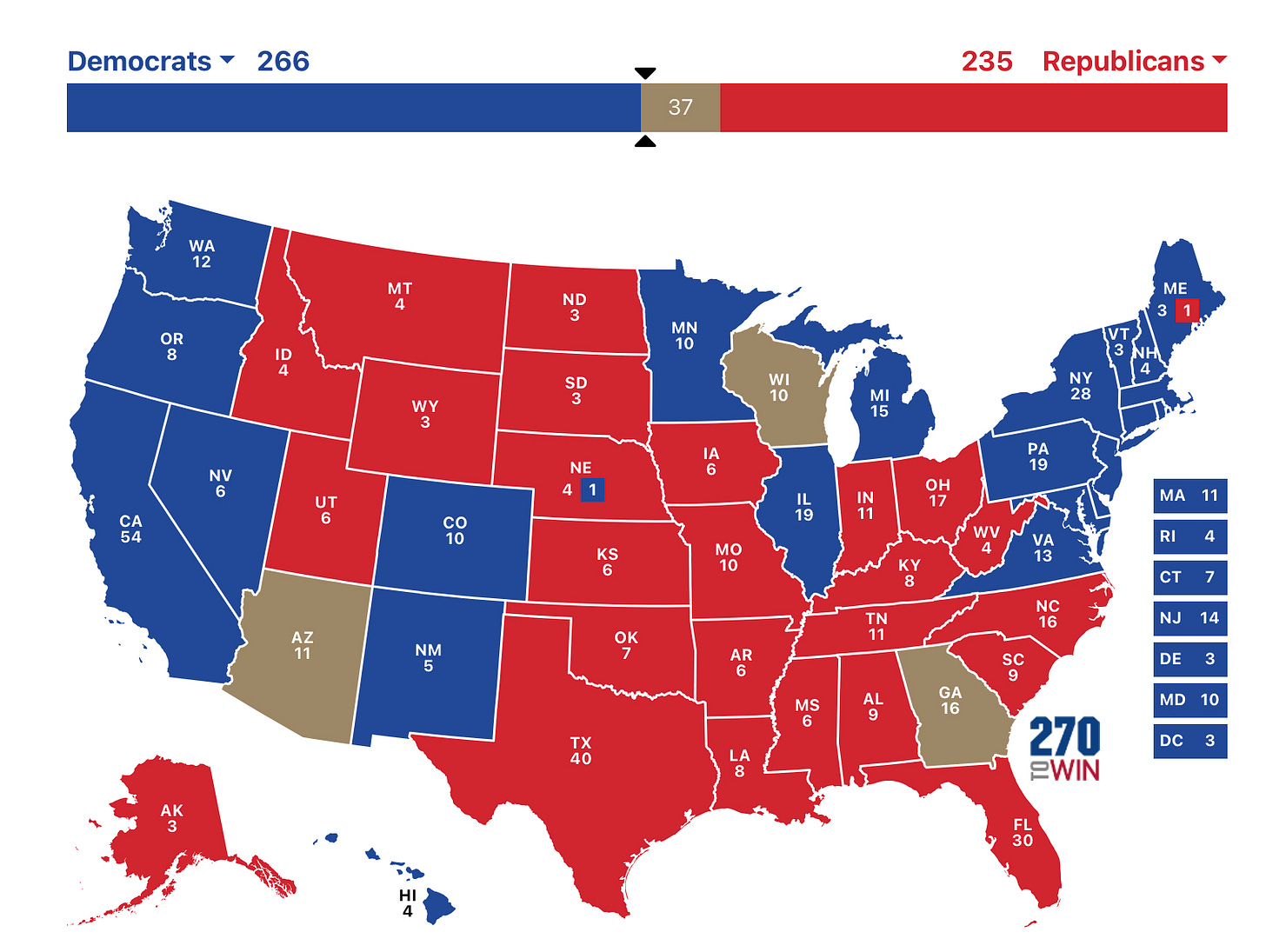

For the Electoral College in 2024, the answer is simpler: States that have traditionally voted Republican (and that did so twice in the past two elections) will gain net three Electoral College votes, while states that voted Democratic in 2020 will lose net three. But this small change actually narrows the pathway for Democratic victory. As Nate Cohen of 537 noted, “It is no longer true that whoever wins three of PA/MI/AZ/WI/GA wins the presidency, as was true in 2020, provided other states vote as they did. Now, Dems can’t win with three smaller states--MI/WI/AZ or GA/WI/AZ.”

The good news is that this still means that a win by Dems in 2024 in any one of the close 2020 races in Georgia, Arizona and Wisconsin would put the Democratic ticket over the top with more than 270 electoral college votes, assuming the swing states of PA and MI also vote the way they did in 2020. This map I generated using the new electoral college vote allocations shows this:

For control of the House, the answer is more complex. We need to look at how the process of reappointment meshes with the related process of redistricting, particularly how the unsavory and problematic process of gerrymandering (that is, drawing districts to maximize political representation by a party) will continue to skew the numbers in favor of the GOP. Today, I just want to focus on apportionment, and I’ll cover redistricting and gerrymandering later.

Every ten years, we reapportion the make-up of the House based on the decennial census. At the outset, it’s important to note that the reapportionment process already favors smaller, more rural states. We’re all familiar with how the Senate make-up gives an advantage in representation to smaller states that is disproportionate to their population: Rural, red-leaning states like Wyoming, North and South Dakota, Idaho, Nebraska and Montana each get two senators, usually GOP ones, despite having a fraction of the population of more far more populous states like New York and California. What is less understood is that over- and underrepresentation in Congress takes place in the House as well, but to a lesser extent because of the way “fractional” House seats are divvied up.

The U.S. has a population of 331 million people according to the 2020 census, up around 7.4% from 2010. With 435 House members, that’s an average of one representative for every 760,000 people. But we can’t just divide by that number and hand out seats based on the nearest rounded up or rounded down number. That could easily result in leftover seats (if too many were rounded down) or not enough seats (if too many were rounded up), so there has to be some other way to decide how those seats are apportioned.

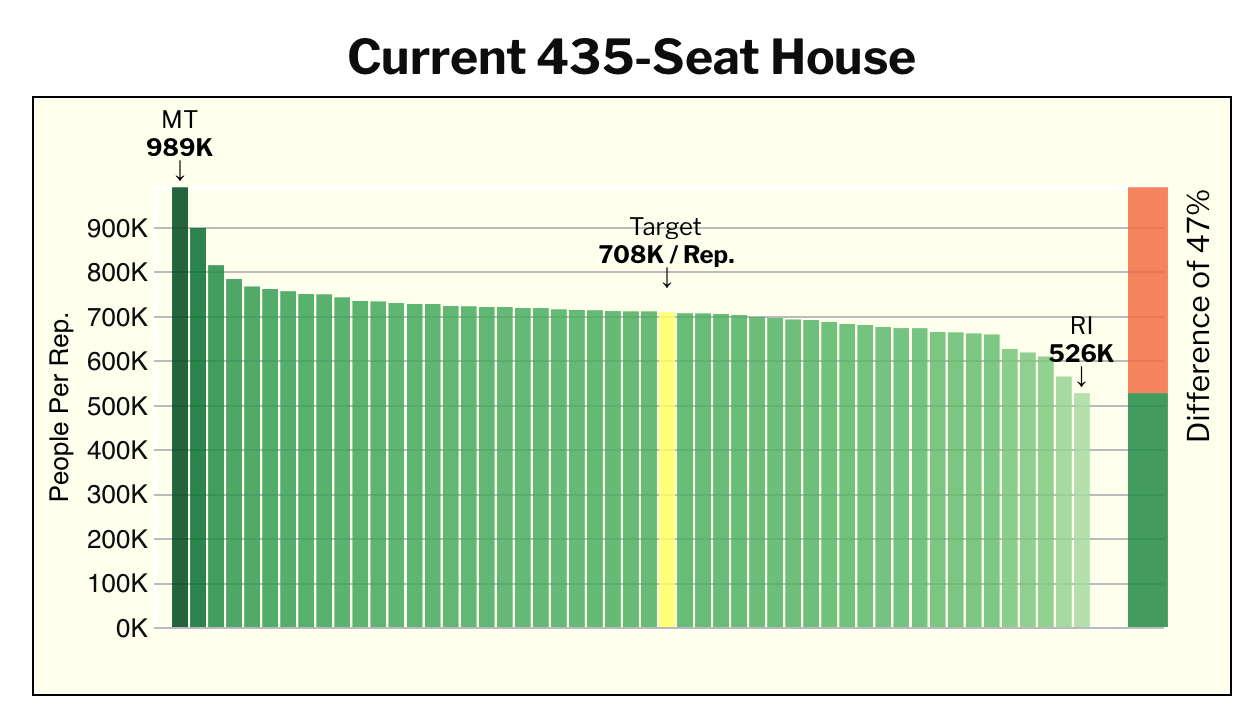

Further, under the Constitution, every state gets at least one House seat no matter what. For example, Wyoming only has 563,000 people in it, according to the 2020 census. This means that nearly 200,000 other people’s strictly proportional right to a House seat will have to be diluted because Wyoming is by design and definition overrepresented. Similarly, Montana, which has 1.08 mil people according to the census, now gets two House seats, or an average of 1 seat for every 504,000 people, because of the way the apportionment process works. By contrast, California actually grew by 2 million people since 2010 but lost a House seat, going from 55 down to 54, due to the math. It simply didn’t grow quite as quickly as it needed to.

Before leaping to the conclusion that this is unfair, we should note that Montana has long only had one House member, despite having 989,000 people, a clear underrepresentation. Meanwhile, tiny Rhode Island, which has only 1,050,000 people, has had two seats for the last 10 years, as this chart shows:

The mathematics behind apportionment were set by law and have remained unchanged since 1941. How we got to this involves a combination of historical back-and-forth (Hamilton and Jefferson fought over this a great deal—Jefferson prevailed and slave-holding Virginia got one more seat for a time) and some complex math that actually uses square roots. The process assigns seats according to a “priority value” which is determined by multiplying the state’s population by a certain amount. After the first 50 seats are assigned, the 51st seat will go to the state with the highest priority.1

Experts have shown how the 1941 method actually winds up favoring small states over large ones, but it isn’t likely to change given our divided politics. A fairer system would increase the number of House seats so that there isn’t such disproportionate representation. The number of House seats has been set at 435 since 1929. Since then, the population has more than tripled and so we really should be looking at an increase in the number of representatives. But that isn’t likely to happen given our currently divided politics.

The shift of House seats from blue states to red (likely also a net shift of three) could result in loss of control of that chamber by the Democrats who hold an already narrow majority. This risk will be further exacerbated by the way that redistricting will play out in GOP-controlled and gerrymandered states. More on that soon.

Math nerds: Under this system, any quotient should be rounded up if it exceeds the geometric mean—meaning the square root of the product—of the two nearest whole numbers. Using this method, a quotient of 2.45 would yield three seats. (The square root of 2×3=6 is 2.449, which is less than 2.450.) If you care to review the math, it is here.