The Perils of Mike Pence: A Quick Civics Lesson

The news lately out of the D.C. federal district courts and Court of Appeals has been pretty terrible for Trump and his allies. Last week, top Trump acolytes, including former chief of staff Mark Meadows and Trump’s lawyer for the Mar-a-Lago top secret/classified documents case, Evan Corcoran, were ordered by outgoing chief district court Judge Beryl Howell to testify before two different federal grand juries.

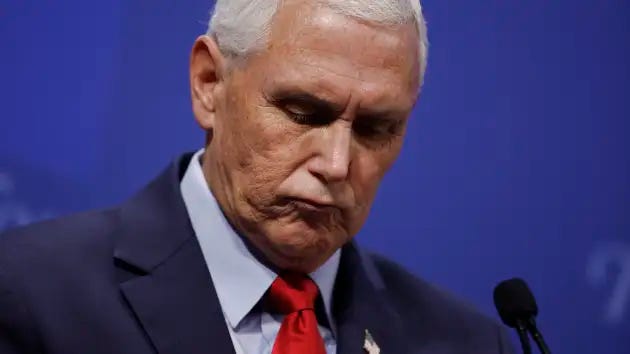

And just yesterday, former vice president Mike Pence was also ordered to testify, this time by the new chief district court judge, the Hon. James E. Boasberg.

Trump’s advisors and Mike Pence have been fighting Smith’s grand jury summons over the past few months in various motions filed under seal. But sources familiar with the proceedings, according to the New York Times and other news outlets, revealed that things did not go particularly well with any of the attempts to block the testimony.

These rulings provide a fine lesson in civics. All three branches of government are involved because the arguments raised by Trump’s allies cover assertions before the judiciary of both executive and legislative privileges. And the question of how our justice system should respond when officials veer into areas of criminality under the guise of such privileges is squarely presented.

So let’s get a little nerdy and take in a quick lesson on checks and balances. Specifically, let’s review how the judiciary can move to place limits on privileges asserted by co-equal branches of government in order to nudge justice along.

The district court shot down Trump’s claims of executive privilege

Trump and his allies hired a bunch of lawyers to try to stop key members of his administration from having to testify before the two federal grand juries. Why? Because based upon from testimony they already gave to congressional investigators, the evidence and knowledge in their possession could land Trump in very big trouble.

Nowhere is this more likely than with former chief of staff Mark Meadows. He was one of the principal go-betweens for the White House and others who were trying to keep Trump in power, including congressional Republican allies, “Stop the Steal” rally organizers, alternate slates of electors in several battleground states, and shady Justice Department officials like Jeffrey Clark.

Remember, Meadows only turned over some of his text messages and records to Congress, then abruptly stopped cooperating and withheld further document production for unclear reasons. Meadows also has never testified before congressional committees about his key role in the alleged conspiracy to obstruct the electoral count, or the conspiracy to defraud the United States by assisting in knowingly spreading false claims of a stolen election.

The thing keeping Meadows from showing up to testify was his (and Trump’s) assertion of “executive privilege.” This court-recognized privilege exists in order to allow candid discussions between presidents and their advisors. After all, if every communication were later to become Exhibit 1 in a court case or congressional hearing, it would stifle the free exchange of advice and discourage candor between presidents and their advisors. But even so, it has some important limitations.

First, the privilege belongs chiefly to the sitting executive. That person is no longer Donald Trump but the current president, Joe Biden. And his White House, after due consideration, has waived executive privilege with respect to communications around efforts to overturn the election.

Second, even to the extent former presidents and their advisors have some limited right to executive privilege, this applies only where the communications were made in an official capacity or were made between advisors and the president. Meadows can’t reasonably claim executive privilege, for example, over communications he had with people other than Trump, such as his top aide Cassidy Hutchinson, about the lead up to January 6.

Third, just as with the far stronger attorney-client privilege, claims of executive privilege cannot shield communications about illegal or fraudulent acts. Interestingly, Judge Howell ruled that Trump’s lawyer, Evan Corcoran, must testify because the government had made its case that the “crime-fraud” exception to the attorney-client privilege applied. This likely meant Judge Howell believed Corcoran was in some way a party to Trump’s attempts to illegally obstruct justice.

That’s quite a bombshell because it also necessarily means that the Justice Department is actively pursuing the crime of obstruction against Trump and has the goods to at least convince a federal judge that it was more likely than not committed by Trump.

Jack Smith’s office may have made similar arguments to get past the executive privilege claims of some of Trump’s allies. For example, and hypothetically speaking, Mark Meadows’s claims of privilege might have failed, at least in part, because the government has shown that his communications with Trump furthered criminal conspiracies to obstruct the electoral vote count and defraud the United States. Whiel this may seem a stretch, Smith has already shown he is willing to fight mini-battles over the whole enchilada, and to convince a judge that a crime was “likely” committed in order to compel a Trump lawyer to testify before the grand jury. So for Smith to make the same argument against Meadows is not out of the realm of possibility.

All we know at this time is that whatever arguments Smith made, they worked with Judge Howell, and now they are working with Judge Boasberg. The prospect of having Trump’s top officials and lawyers all go before the grand juries under oath is not only historically remarkable, it is a highly damaging development for the ex-president.

Mike Pence’s claims of legislative privilege are weak sauce

Monday’s ruling by Judge Boasberg dispensed quickly with Trump’s efforts to claim that executive privilege shielded Pence and other Trump White House officials from having to testify.

But as I wrote about back in February, Pence had also asserted a new, novel theory to seek to prevent his testimony before the grand jury. Pence argued that the “Speech or Debate” clause of the Constitution protected him and prevented disclosure of his words and actions when it came to his role in counting the votes.

If this sounds vaguely familiar, it’s the same argument that Sen. Lindsey Graham raised, unsuccessfully, to try and prevent his testimony before Fani Willis’s investigative grand jury in Fulton County, Georgia.

The Speech or Debate clause generally shields legislators from being answerable in courts for their words on the floor of Congress. It has also been extended to things like speech outside of Congress made in the course of legislative fact-finding. It reads as follows:

The Senators and Representatives…. for any Speech or Debate in either House [ ] shall not be questioned in any other Place.

Pence’s attorneys cleverly pointed out that his role on January 6 was a “president of the Senate.” Therefore, they argued, he was acting in a legislative capacity on January 6 and his communications about his role ought to be protected under the “Speech or Debate” privilege.

So, how strong of a privilege is this right for legislators (or people acting like legislators) to not “be questioned in any other Place”? That depends on a few considerations.

First, courts will want to know whether the communications at issue were made in the course of regular duties as a legislator or if they were outside of it. Just because Pence was Senate president for that day doesn’t mean all of his communications are magically protected. For the privilege to apply, his communications would have to fall inside of the scope of those duties, which in this case were largely ceremonial.

Second, courts do not want to countenance hiding illegal communications behind legislative privilege. This is a lot like the “crime-fraud” exception discussed above. For example, if a senator takes a bribe in order to vote a certain way on a bill, communications about that bribe are not protected by the Speech or Debate clause.

Judge Boasberg appears to have applied both of these principles in ordering Pence to testify.

While rejecting Trump’s sweeping claims of executive privilege, Boasberg found that Pence possesses a limited legislative privilege based on the Speech or Debate clause. Pence therefore doesn’t have to provide records or answer certain questions so long as they align with his narrow duties as president of the Senate overseeing the certification of the election on January 6, 2021. But the privilege, Boasberg also ruled, does not extend to any questions that implicate any illegal acts or requests by Trump.

If you feel like that is an exception you could drive the Trump train through, you would be correct.

After all, the questions that really matter to Jack Smith and his grand jury are the ones that implicate illegal acts by Trump. These include, notably, requests by Trump for Pence to exceed his constitutional authority and declare the election for his boss, or otherwise “send the votes back” to the GOP state legislatures where Trump had cultivated support.

It would be a powerful and likely indictment-sealing moment to have the former vice president tell the grand jury, under oath, that the former president personally demanded that he break the law and hand him the election. We all know it happened, but having it come from Pence’s mouth would be shattering to Trump.

Mike Pence really does not want to have to say this out loud, let alone to a grand jury, but that moment is ever closer now. Pence instead was hoping to drag this out and never have to show up, but Judge Boasberg didn’t play along; he issued his ruling just four days after the hearing. And recent quick actions and even overnight briefing schedules ordered by the D.C. Circuit on emergency Trump appeals may further burst Pence’s delay bubble. As arch-conservative jurist and ardent Trump critic Judge Michael Luttig wrote in a surprisingly sharp OpEd for the New York Times,

If Mr. Pence’s lawyers or advisers have told him that it will take the federal courts months and months or longer to decide his claim and that he will never have to testify before the grand jury, they are mistaken. We can expect the federal courts to make short shrift of this “Hail Mary” claim, and Mr. Pence doesn’t have a chance in the world of winning his case in any federal court and avoiding testifying before the grand jury.

This presumably includes the Supreme Court.

If one of the most conservative judges in the country is publicly writing this about Pence’s case, after personally advising Pence not to obey the unconstitutional directive of Trump in the days leading up to January 6, Pence may well decide that an appeal isn’t even worth it.

On the other hand, Pence may appeal the ruling anyway, because as a presidential candidate himself, his chief goal today is to impress upon MAGA voters that he’s doing everything he can to not throw Trump under the bus.

But ultimately, and not long after he exhausts any appeals, Pence may well have to do precisely that before Smith’s grand jury.

Excellent analysis. My own wonder is whether the judge threw Pence the bone of the speech and debate clause issue in order to a) limit the attractiveness of appeals. It is clear that executive privilege is going nowhere in the courts, and you can't appeal a point you asked for. and b) to keep the supremes from getting their grubby hands on this new take on speech and debate. After all, the only argument that can be made on appeal from the judge's ruling is that the clause does indeed protect you from talking about people urging clearly illegal acts.

The most interesting question for me is whether Meadows will invoke his 5th amendment right against self-incrimination and, if so, whether the Special Counsel will immunize Meadows or try to use the testimony of others to build a case against Meadows and force him to cooperate. Jay, what do you think happens re: Meadows?