We Need To Bust Some Myths About Police Killings.

Because we can’t solve a problem that we don’t adequately understand.

Police shootings are on a lot of minds today following the homicide of 20-year old Daunte Wright at the hands of the Brooklyn Center police in Minnesota, just 10 miles from where George Floyd was killed. Because police database records across the country tend to underreport cases, independent press and think tank efforts got underway years ago, following the turmoil in Ferguson, to accurately track what is happening with these killings. The statistics are sobering and important because they dispel several common myths. I’ll discuss three today.

Myth 1: Most victims were involved in a violent incident.

There is a tendency to see homicides that occur at the traffic stops, mental health crises and misdemeanor offenses as aberrations, the inevitable result of the need for police to maintain readiness and use force in the face of a violent and dangerous criminal environment. It surprises many to learn that a solid majority of police killings occur in non-violent settings.

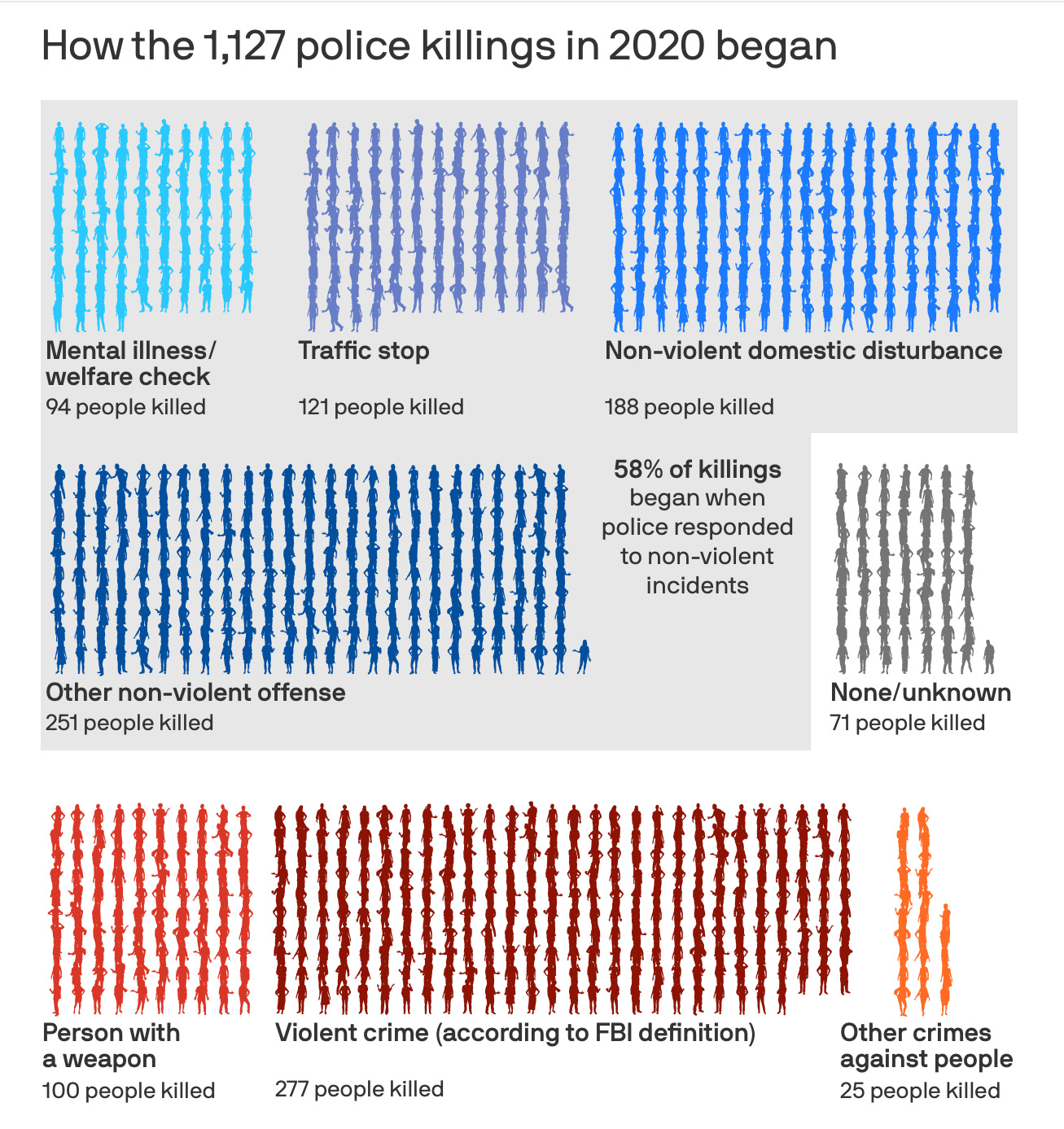

Of the 1,127 police killings that took place in 2020, 58% of them began as non-violent incidents, according to the Mapping Police Violence project. Nearly 20 percent of them involved routine traffic stops or mental health interventions, and another 15 percent or so began as non-violent domestic disturbances. Another 20 percent fell under other non-violent offenses. Here is a chart from Axios of how the 2020 police killings broke down:

Given these statistics, it’s unsurprising that police encounters generate trepidation and fear in minority communities. A routine traffic stop, which according to his mother is what Daunte Wright believed was happening to him, could end in death. Every family crisis that escalates is a roll of the dice if the police become involved in any way.

Myth 2: Things are getting better as more attention is paid to police violence

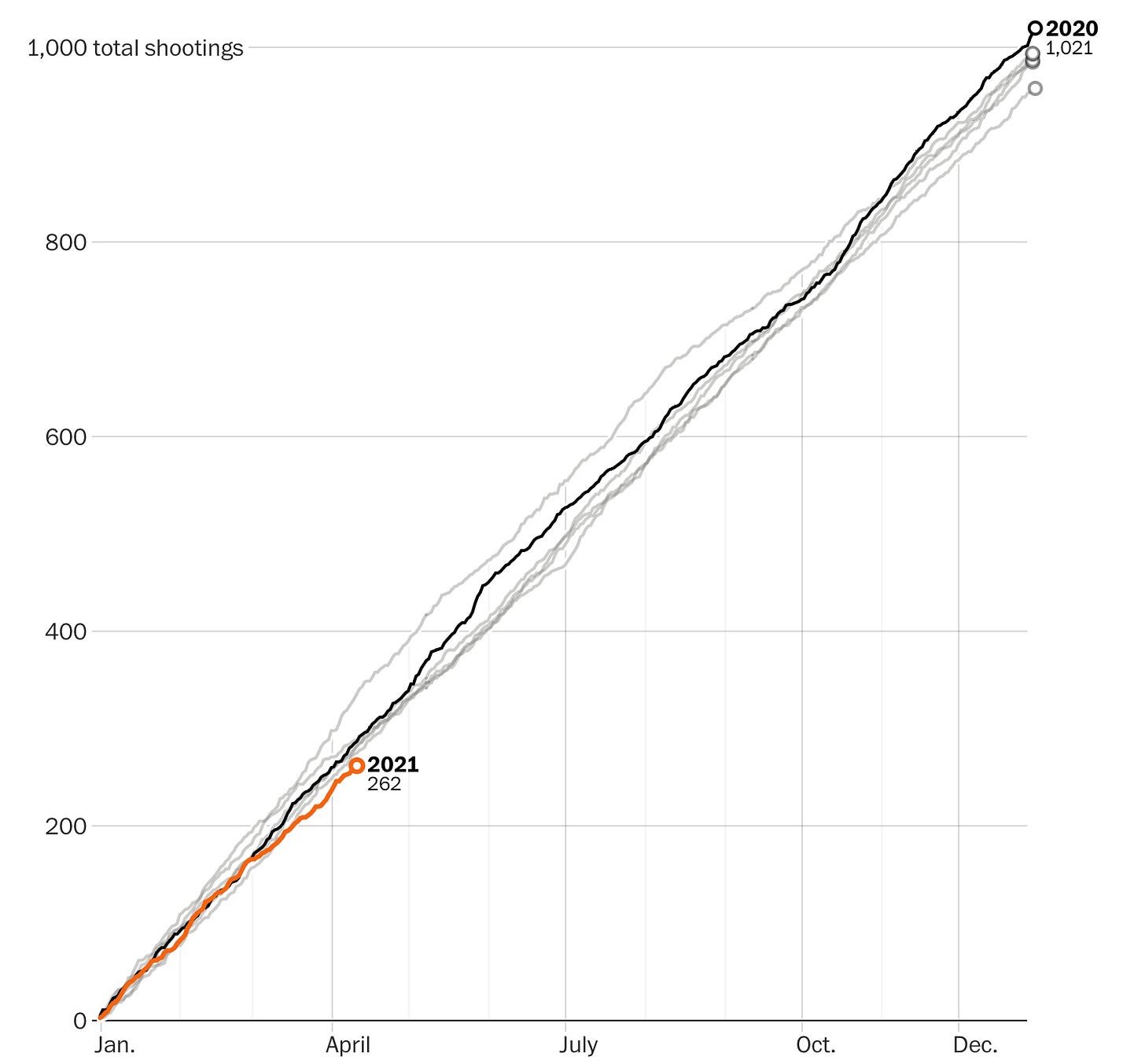

The sad truth here is that the number of killings perpetrated by the police has remained stubbornly consistent and high for as long as the numbers have been tracked. 2020 wound up with numbers similar to prior years, and 2021 is mapping the exact same trajectory. Here are the numbers. You can see 2021 in the lower left corner, following the steady line upward already.

One shift however is where the killings are taking place. Police violence is dropping in major urban areas, but it is rising in suburban and rural areas. This might indicate that reforms and training are having an effect, but that we need to do more work outside of the cities as well.

Myth 3: African Americans are not killed any more frequently and are more likely to be armed.

Right-wing media and politicians often push the statistic that more white Americans are killed each year than black Americans, and therefore the system is not systemically racist. This is just bad math, used to promote an agenda and shroud the awful truth. According to a study by the Washington Post, from 2015 to 2020, while half the people shot and killed by police were white, African Americans were killed at a disproportionate rate because they only comprise 13 percent of the population. Specifically, black Americans are killed at more than twice the rate of whites.

But isn’t this just a function of the danger that police are actually in when arresting a Black suspect? The answer again is no. In the police killings tracked from 2013-2020 by the Mapping Police Violence project, Black suspects were 1.3x more likely to be unarmed relative to white suspects.

Daunte Wright was one of these unarmed arrestees, reportedly pulled over for expired registration tags, but (and to his mind probably inexplicably) hauled out of his car by the cops and was about to be handcuffed. An arrest warrant for failure to appear at a remote hearing (the notice of which apparently had been sent to the wrong address) had tagged him within the system. That system failed Wright in many ways, driving him to fear otherwise routine traffic stops by the cop as most young Black men understandably do, then ending his young life at the hands of an officer who now claims she didn’t know she had drawn her gun rather than her taser, firing on him as he was trying to escape.

And statistically speaking, the officer is very unlikely to be held accountable for Wright’s homicide or for that matter even be charged. From 2013-2020, 98.3% of police killings did not result in the officer behind charged with a crime, according to the Mapping Police Violence Project.

Daunte Wright thus will likely simply become yet another grim statistic in an unrelenting and deadly system of police violence.

Shouldn’t the analysis also take account of the number of police encounters with the population in question? Of course, some police encounters with people of color are manufactured through selective enforcement of broken-taillight and dangling-deodorant rules and other pretexts. But many, presumably, are not.

To determine if race was a bias in a shooting we would have to know the number of interactions with police not the general population. Since every interaction with police is not a likely number we can obtain as police are not required to record every interaction we can use Police Arrests as a proxy for interactions. When you use actual arrests demographics and compare them to shootings you find that black people are not in fact shot at a higher rate. This is an important step in inference because the solution to the problems is inherently different. This means that the number of stops and/or arrests are at a higher frequency which leads to higher shot rates which could be from implicit bias of the officers, systemic issues such as a prevalence to socioeconomic factors that are correlated with higher crime, or a combination of the two. If it is merely a systemic issue teaching cops to stop being racist doesn't solve the problem. If it is a police are bias/racist issue solving systemic issues won't solve the problem.