On Sunday evening, Judge Tanya Chutkan surprised many with a Minute Order entered on the docket. That order lifted an “administrative stay” on the court’s gag order and denied Defendant Trump’s motion to stay the order pending appeal.

Don’t feel bad if you’re confused by this. What it means, in plain English, is that Judge Chutkan’s limited gag order is back in place. Trump is now barred from making, or directing others to make, certain kinds of threats against attorneys, court staff, or witnesses or the subject of their testimony.

But wait, what happened that it was not in place? And what caused her to change her mind and reinstate it? Is this related to the other gag order? What has Trump said or done since? And are we going to wind up back in court on this?

Today, we discuss all things gag order, and I will try to address the most common questions I have seen around this subject. I’ll try my best to lay it all out without using too much technical jargon. And I’ll zoom out a bit at the end and explain why this is so darned hard to get right in this case.

Gag orders versus pre-trial release conditions

To understand the full nature of limitations on Donald Trump now that he is a criminal defendant, we need to understand the difference, and the overlap, between a so-called gag order and what are known as “pre-trial release conditions.”

The latter is an agreement between a defendant (like Trump) and the Court that he will be released pending trial—that is, not held in detention—provided he abides by certain conditions. These include not discussing the facts of the case with potential witnesses and not violating state or federal laws. The last part can include, as Judge Chutkan has noted, laws against witness intimidation. Violations of the pre-trial release conditions can result in sanctions, from fines up to revocation of the agreement, which would land Trump in detention pending trial.

A gag order is far more specific and usually gets put in place by way of a request by the state. The specificity of the gag order allows the court to zero in on the kinds of speech limitations it will impose. This is important because broad and vague prohibitions risk running afoul of the First Amendment, so judges are usually careful to build a solid factual record and tailor the gag orders as narrowly as possible to avoid charges of free speech violations.

It’s helpful to think of the pre-trial release conditions as something of a hammer and gag orders as a more refined tool that can put the screws to a defendant. It is not uncommon for that hammer to be used, even in high profile cases. For example, Sam Bankman-Fried’s bail was revoked and he was sent to prison after a judge found he had violated his pre-trial release conditions by seeking to influence witnesses. Judge Amy Berman Jackson threatened to send Roger Stone to pre-trial detention in response to him posting an image of her in cross-hairs on Instagram; after a hearing, she instead imposed a gag order, which he proceeded to violate, resulting in her removing his right to post on social media up to and through the trial.

In Trump’s D.C. case, Judge Chutkan has imposed a “limited” gag order that gets at the kinds of harms she is trying to stop.

It prohibits Trump from making public statements that “target” individual attorneys, court staff, witnesses or “any reasonable foreseeable witness” involved in the case or the substance of their testimony.

On, then off, then on again

There was a procedural quirk that needs a bit of explaining. Jack Smith moved for a protective order (which Judge Chutkan herself refers to as a gag order, so we’ll use that term). After a hearing in which several examples of Trump’s inflammatory posts and speech were entered into the record, Judge Chutkan issued a limited gag order.

A furious Trump filed notice of an appeal, and then his lawyers asked for a what’s called a “stay” of the order—meaning, putting the gag order on hold—pending resolution of the appeal. Judge Chutkan, choosing the path of caution, voluntarily placed her own gag order on hold and invited the parties to argue why it should or should not remain in place while the appellate court heard the case.

Trump made her decision easy. While the gag order was temporarily on hold, and in the middle of the parties briefing the issue, Trump proceeded to attack his former chief of staff, Mark Meadows, in a social media post on Truth Social. Trump had no doubt heard about or read a scoop by ABC News that Meadows had met with prosecutors and agreed to testify before the grand jury under an immunity deal. Whether that story is accurate was disputed by Meadow’s lawyer, but there is no doubt about the nature of Trump’s threat to Meadows and other witnesses.

After that story broke, Trump posted that he wouldn’t expect Meadows to “lie about the Rigged and Stolen” election “merely for getting IMMUNITY” but added that “Some people would make that deal, but they are weaklings and cowards, and so bad for the future of our Failing Nation.”

Jack Smith’s office cited the threat in their court filing in favor of reinstating the gag order pending appeal, arguing that even the temporary lifting of the gag order had given Trump a chance to renew attacks on witnesses such as Meadows. Trump has a practice of using “external influences to distort the trial in his favor” and a “long and well-documented history of using his public platform to target disparaging and inflammatory comments at perceived adversaries.” When he does so, “harassment, threats, and intimidation foreseeably and predictably follow,” Smith's team wrote. That includes a recent death threat against the judge herself.

“These actions, particularly when directed against witnesses and trial participants, pose a grave threat to the very notion of a fair trial based on the facts and the law,” Smith’s team warned.

Interestingly, Smith’s team also cited two violations of the gag order placed by Judge Engoron in the civil fraud trial now pending in New York as a way of showing how Trump routinely violates court orders. Trump has been fined twice for a total of $15,000 and threatened with jail time for making sideways threats on the internet against the judge’s law clerk, whom he falsely suggested was Majority Leader Chuck Schumer’s girlfriend because they were photographed together.

Judge Chutkan’s order reinstating the gag order

As I was writing this, Judge Chutkan released her opinion and reasoning behind lifting her self-imposed stay and reimposing the gag order. She noted that, had her order been in place, Trump’s attacks upon Meadows would “almost certainly” have been in violation of her order because it singled out a potential witness and cast his probable testimony as a “lie.”

She also emphasized that the order did not abridge Trump’s First Amendment rights and was in fact required of her under the local rules, the federal criminal procedural rules and Supreme Court precedent.

Trump will be back at it soon

These violations demonstrate that no matter how narrow the gag order, Trump will poke at its edges and push its limits, daring the court to act. It pretty much assures observers that Trump will be back before Judge Chutkan soon on another violation.

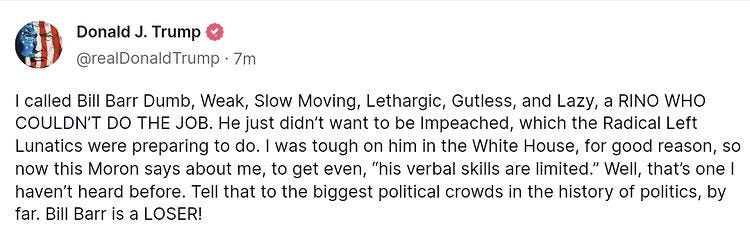

Indeed, after Judge Chutkan’s minute order reinstating the gag order went out Sunday night, Trump appeared to violate it again by attacking his former Attorney General, Bill Barr, who presumably is a key witness against him in the trial, as “Dumb, Weak, Slow Moving, Lethargic, Gutless, and Lazy, a RINO WHO COULDN’T DO THE JOB.”

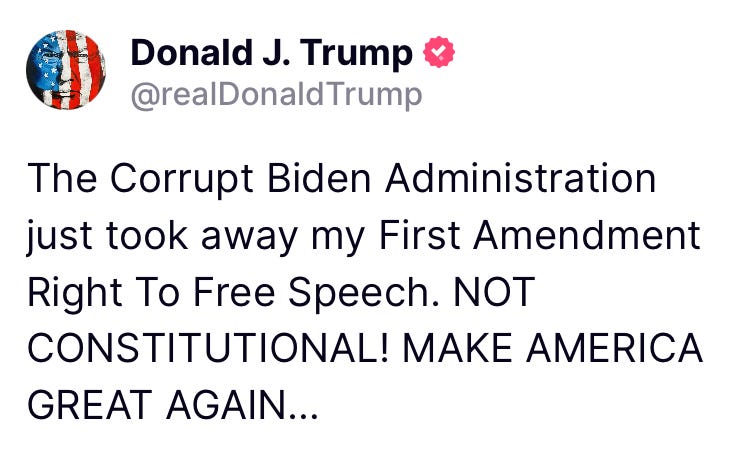

It is unclear whether Trump had notice of the order at the time of this threat; once he learned that it was reinstated, he whined very publicly about it once more, writing, “The Corrupt Biden Administration just took away my First Amendment Right To Free Speech. NOT CONSTITUTIONAL! MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN…"

So now what?

Much of Trump’s defense in the case, both in the courtroom and in the public arena, relies on an absolute freedom of speech argument—freedom to speak lies, to threaten officials, and apparently to intimidate witnesses, all because he is a politician who once was president and wants to be again. These aren’t legally strong arguments, but they resonate deeply with his followers, who believe Trump should have the right to fight back against the system that is seeking to jail him, and that he is entitled to use whatever means he has.

From a legal standpoint, Judge Chutkan (and Judge Engoron) would be within their rights to sanction Trump, including slapping him with jail time. As a criminal defendant under conditions of pre-trial release, Trump’s “freedom of speech” is already curtailed, and as Judge Chutkan noted in her opinion, judges have a right, indeed an obligation, to ensure the orderly administration of justice. That includes preventing defendants from tainting the process, either through jury pool manipulation or witness influencing and intimidation. With active threats already made against court personnel, there is an added urgency and need for restraining the speech of a defendant like Trump.

From an administrative and public good standpoint, however, sanctioning Trump or even jailing him poses real challenges. For example, there is the question of how to keep him secure in any facility and what to do with his presidential security detail, who legally can’t be ordered to jail along with him. And any severe sanction, such as jail time, would threaten to turn the court proceedings into a circus, possibly eclipsing the underlying charges while elevating Trump to near martyrdom amongst his devoted followers.

Trump has clearly made the calculation that defying gag orders in a way designed to give himself plausible outs each time (“I was talking about Michael Cohen, not about your law clerk!”) is working well for him. It keeps him in the news, it riles up his followers, it leads to more donations, and it distracts from the underlying crimes and cases. With all this in mind, judges are understandably reluctant to give him more of what he wants. At the same time, they need to rein him in while building a record of his misdeeds that makes their orders and sanctions appeal-proof. Judge Chutkan stated in her order that she would have to consider the substance and context of any future violations and invite the parties to present argument. That is a sensible and understanbly cautious approach.

We should assume that whatever limitations a judge seeks to impose, Trump will violate them. But there’s an opportunity to get a little creative. For example, Judge Chutkan could suspend his ability to post on social media, if even for a week, as Judge Jackson did to Roger Stone. Of course, how to enforce this the moment he inevitably finds a way to violate that restriction remains unclear.

To those understandably clamoring for Trump to be silenced completely and jailed immediately, consider this: Much as we’d love to treat Trump like “every other defendant,” he simply is not. Restriction on the speech or even the liberty of a major political party’s leading candidate for chief executive carries political and constitutional ramifications that courts have never dealt with before. This could lead to potential reversal of sanctions or gag orders by higher courts, including the conservative Supreme Court. The drama and chaos around such a move could even lead to an argument that he could not receive a fair trial before this court or in that jurisdiction. The last thing either judge issuing gag orders against Trump wants is another basis to overturn a verdict.

That is why, as frustrating as this feels, caution and a ratcheting up of consequences, rather than sending him to jail immediately, make sense. The judiciary as a whole needs to grow weary and hardened against Trump’s antics, just as the public does. And something of a public consensus must also arise that all reasonable options have been exhausted and that harsher sanctions are not only in order but absolutely necessary in light of his flagrant violations.

Gag orders on Trump are a bit like his indictments. It was very big news when the first one dropped, and the right howled in protest over it. But as other grand juries weighed in, the public grew more accustomed to the idea of Trump facing trial, now in multiple jurisdictions. Each set of new indictments drew muter responses from his supporters. This has led to some 45 percent of Republicans polled in August stating they would not vote for him as a candidate if he were convicted, higher than the 35 percent polled who said they would.

A slow roll-up of restrictions and gag orders could similarly box Trump in and allow the public, including his MAGA base, to accept that Trump will be sanctioned and limited in some way. Given the reimposition of the gag order, the next move is his, and there is almost no doubt that he will violate it again. We’ll have to see what the court does in response.

Upon the next violation, Judge Chutkan could issue an order to show cause why his pre-trial release should not be revoked. And then with the threat of jail hanging over him, she could sanction him with a major fine and remove his social media posting privileges, say, for a week. And then warn him it will be worse next time for him, up to and including jail.

Trump—and just as importantly the public—will have been put on notice that he really is pushing it too far, and if he does wind up in jail, that’s on him. And bonus: Having Trump spend even a day or two in confinement would have the added benefit of getting the public used to the idea of Trump in jail, similar to how it got used to the idea of him being indicted.

I like the “major fines“ idea. In the Engeron example, $5000 and then $10,000 are chump change for Trump, and worth the grifting and publicity. If he was hit by a $500,000 or $750,000 fine, that would start to get him where it hurts, and it would be difficult for him to quickly grift that much money back.

The law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to call a judge “corrupt,” “unhinged,” “a nut job,” “grossly incompetent,” a “partisan political hack,” and a “Radical Trump Hater,” but the penalties vary, apparently, depending.